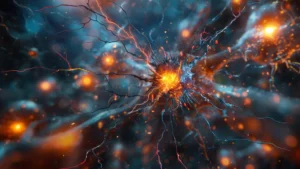

Anxiety disorders affect roughly one in five people in the United States, making them among the most widespread mental health challenges. Although common, scientists still have many questions about how anxiety begins and is controlled within the brain. New research from the University of Utah has now pinpointed two unexpected groups of brain cells in mice that behave like “accelerators” and “brakes” for anxious behavior.

The team discovered that the cells responsible for adjusting anxiety levels are not neurons, which typically relay long-distance electrical signals and form circuits throughout the body. Instead, a specific class of immune cells known as microglia appears to play a central role in determining whether mice show anxious behavior. One subset of microglia increases anxiety responses, while another reduces them.

“This is a paradigm shift,” says Donn Van Deren, PhD, a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Pennsylvania who carried out the work while at University of Utah Health. “It shows that when the brain’s immune system has a defect and is not healthy, it can result in very specific neuropsychiatric disorders.”

The findings are reported in Molecular Psychiatry.

Microglia Show a More Complex Role Than Expected

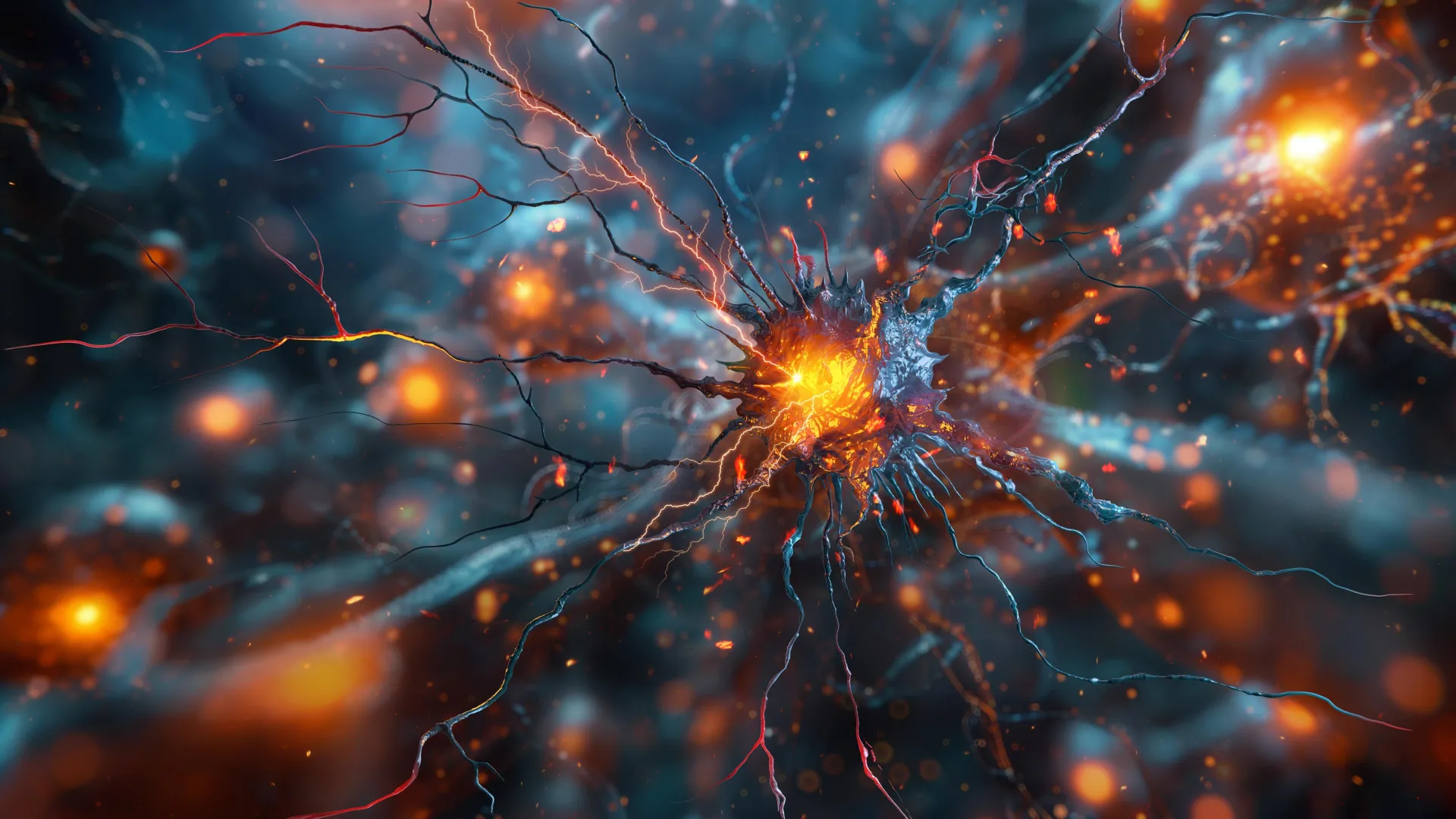

Earlier experiments had already suggested that microglia influence anxiety, but researchers initially believed that all microglia functioned in the same way. When they interfered with a particular subset known as Hoxb8 microglia, the mice began behaving as though they were anxious. However, when researchers blocked the activity of all microglia at once, including both Hoxb8 and non-Hoxb8 groups, the mice behaved normally.

These confusing results led the team to suspect that the two types of microglia might work in opposite directions. Hoxb8 microglia might help prevent anxiety, while non-Hoxb8 microglia might encourage it. To test this idea, they needed to examine each type of microglia on its own.

Testing the Brain’s Internal Anxiety Accelerator and Brake

To isolate each group, the researchers designed an unusual experiment that involved transplanting different types of microglia into mice that lacked microglia entirely.

Their tests showed that non-Hoxb8 microglia function like a gas pedal for anxiety. When the team transplanted only non-Hoxb8 microglia into the microglia-free mice, the animals displayed strong signs of anxiety. They groomed themselves repeatedly and avoided open spaces, behaviors that typically indicate heightened anxiety in mice. Without Hoxb8 microglia present, the anxiety “accelerator” remained active without any natural balancing force.

In contrast, Hoxb8 microglia acted like the braking system. Mice given only Hoxb8 microglia did not behave anxiously. Importantly, mice that received both microglial types also showed no signs of anxiety. Even though non-Hoxb8 cells encouraged anxious behavior, the presence of Hoxb8 cells neutralized those effects.

“These two populations of microglia have opposite roles,” says Mario Capecchi, PhD, distinguished professor of human genetics at University of Utah Health and senior author of the study. “Together, they set just the right levels of anxiety in response to what is happening in the mouse’s environment.”

Implications for Future Anxiety Treatments

According to the researchers, these results could reshape how scientists think about the biological roots of anxiety disorders and how they might be treated in the future. “Humans also have two populations of microglia that function similarly,” Capecchi explains. Despite this, nearly all current psychiatric medications target neurons rather than microglia.

Understanding how these immune cells influence anxiety could lead to therapies that intentionally enhance the braking effect or reduce the accelerator activity. “This knowledge will provide the means for patients who have lost their ability to control their levels of anxiety to regain it,” Capecchi says.

Van Deren adds a note of caution. “We’re far from the therapeutic side,” he says, “but in the future, one could probably target very specific immune cell populations in the brain and correct them through pharmacological or immunotherapeutic approaches. This would be a major shift in how to treat neuropsychiatric disorders.”

The study appears in Molecular Psychiatry under the title “Defective Hoxb8 microglia are causative for both chronic anxiety and pathological overgrooming in mice.”

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, including the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH093595), the Dauten Family Foundation, and the University of Utah Flow Cytometry Facility. The authors note that the content is solely their responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.