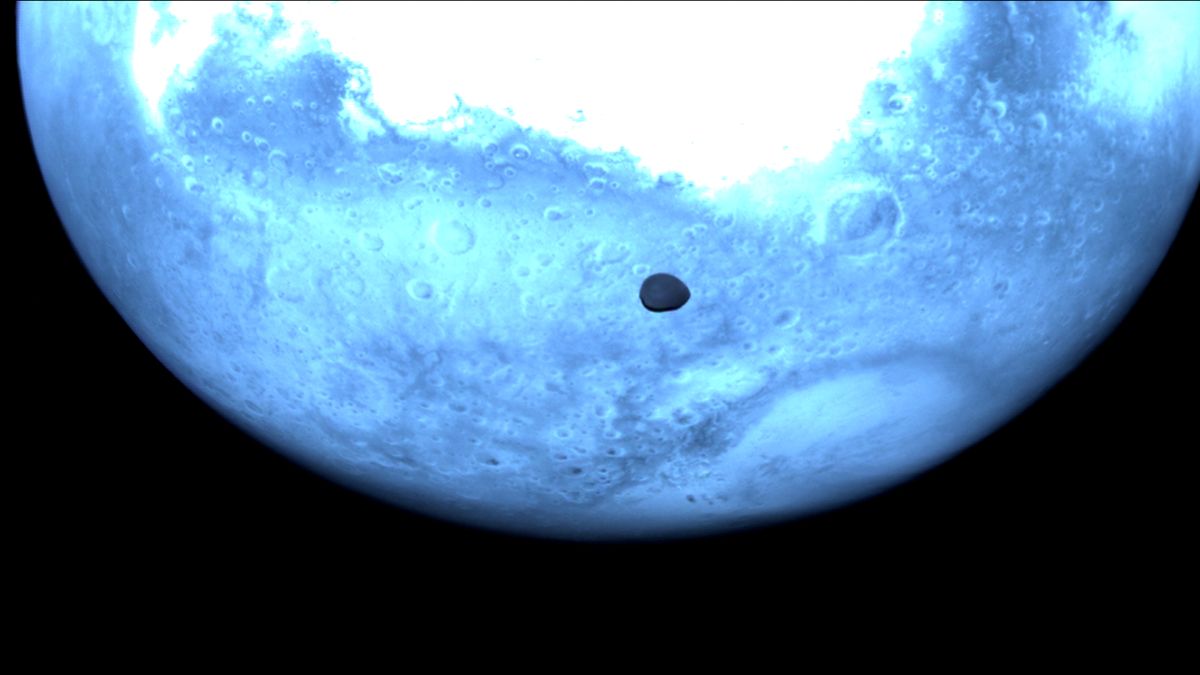

Europe’s Hera mission, on its way to the Didymos–Dimorphos double asteroid system, has performed a close flyby of Mars, receiving a crucial gravitational slingshot, testing some of its instruments, and gaining new images of Mars’ little-seen moon Deimos, which could answer questions about the origin of the Red Planet’s moons.

The flyby took place on Wednesday (March 12), and the European Space Agency presented the images during a webcast today. The images presented show Deimos set against a backdrop of the Red Planet below it as Hera flew within 3,100 miles (5,000 kilometers) of Mars and just 621 miles (1,000 kilometers) of Deimos.

“Last night was a very short night, I think we slept about 3 hours,” said Hera Project Manager Ian Carnelli, of the European Space Agency during the ESA webcast. “But as we flew by Mars this gave us more than a thousand images that are absolutely breathtaking.”

Mars has two moons, named Phobos and Deimos, but because Phobos is closer to Mars, it has been previously imaged by other spacecraft.

“For Deimos, we don’t have as many images as Phobos, so all opportunities to see Deimos are high value,” said Hera’s Principal Investigator, Patrick Michel of the University Côte d’Azur in Nice, France.

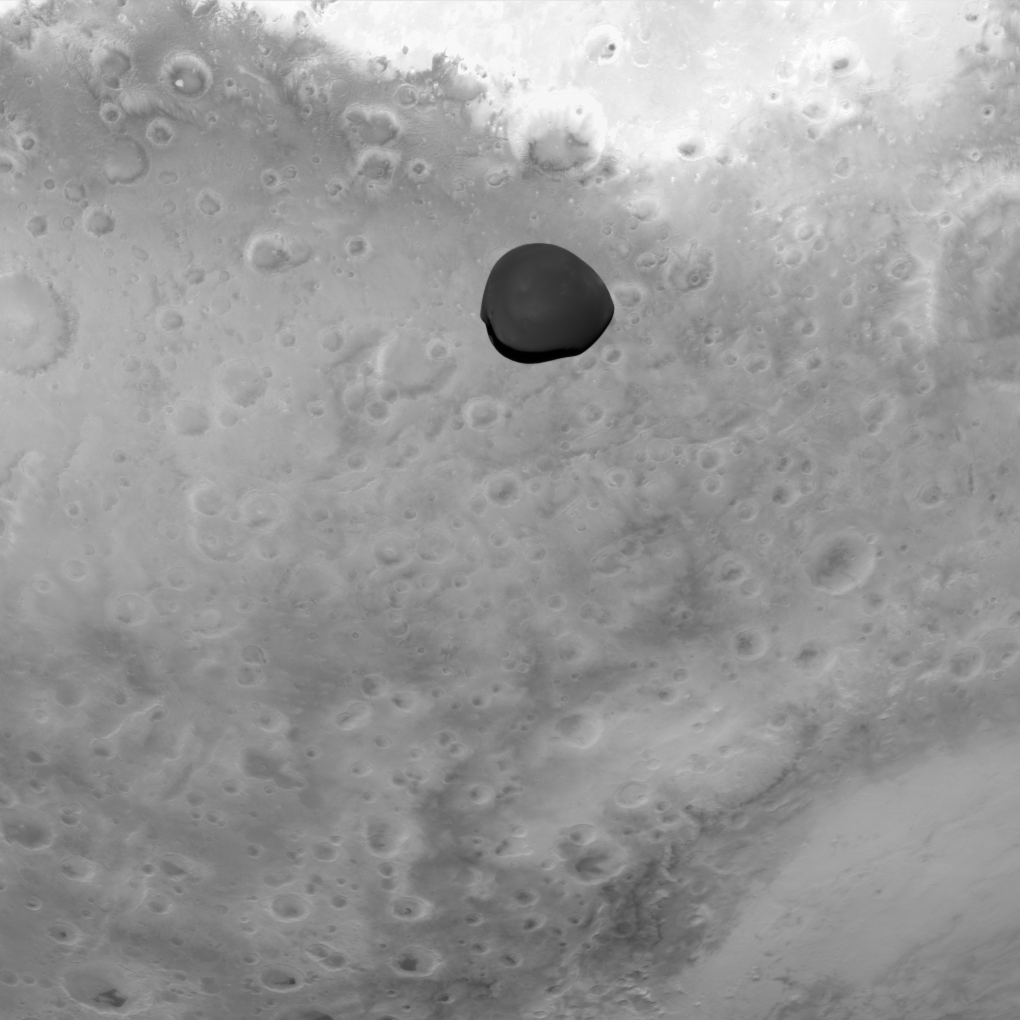

What was also different about this flyby was that the side of Deimos that was imaged. Deimos is tidally locked to Mars, meaning that like Earth’s moon, it continually shows the same face to the Red Planet. Most previous images of the small, 7.7-mile-wide (12.4 kilometers) Deimos have shown Mars-facing side. Before now, only the United Arab Emirates’ Hope mission, which arrived at Mars in 2021, had seen the side of Deimos that faces out into space.

Julia de León, of the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, who leads Hera’s Hyperscout-H multispectral imager, which observes light from celestial objects through 25 filters extending from visible wavelengths into the near-infrared, says these images can reveal the chemical composition of the moon.

“It’s the first images of this face [of Deimos] obtained at these wavelengths,” said de León. With Hyperscout-H, it means that “we can retrieve information about the potential minerals on the surface of Deimos.”

Understanding the composition and make-up of Deimos is important, because we don’t understand the origins of either of Mars’ moons. Both Phobos and Deimos look like asteroids, being lumpy, cratered and small. Therefore, one hypothesis is that they are captured carbon-rich, or C-type, asteroids. However, captured bodies usually end up in eccentric, inclined and often retrograde orbits, whereas Phobos and Deimos orbit Mars in the red planet’s equatorial plane and in prograde fashion.

So an alternative hypothesis is that they formed out of debris that ended up in orbit around Mars following a huge impact on the Martian surface. Then there’s a more recent, third possibility, which is that they could be the remains of a larger asteroid that was torn apart.

Identifying the materials from which Phobos and Deimos are made will offer clues as to how they formed. For example, the presence of basalt would imply their materials came from the surface of Mars, where there has been extensive volcanism in the past.

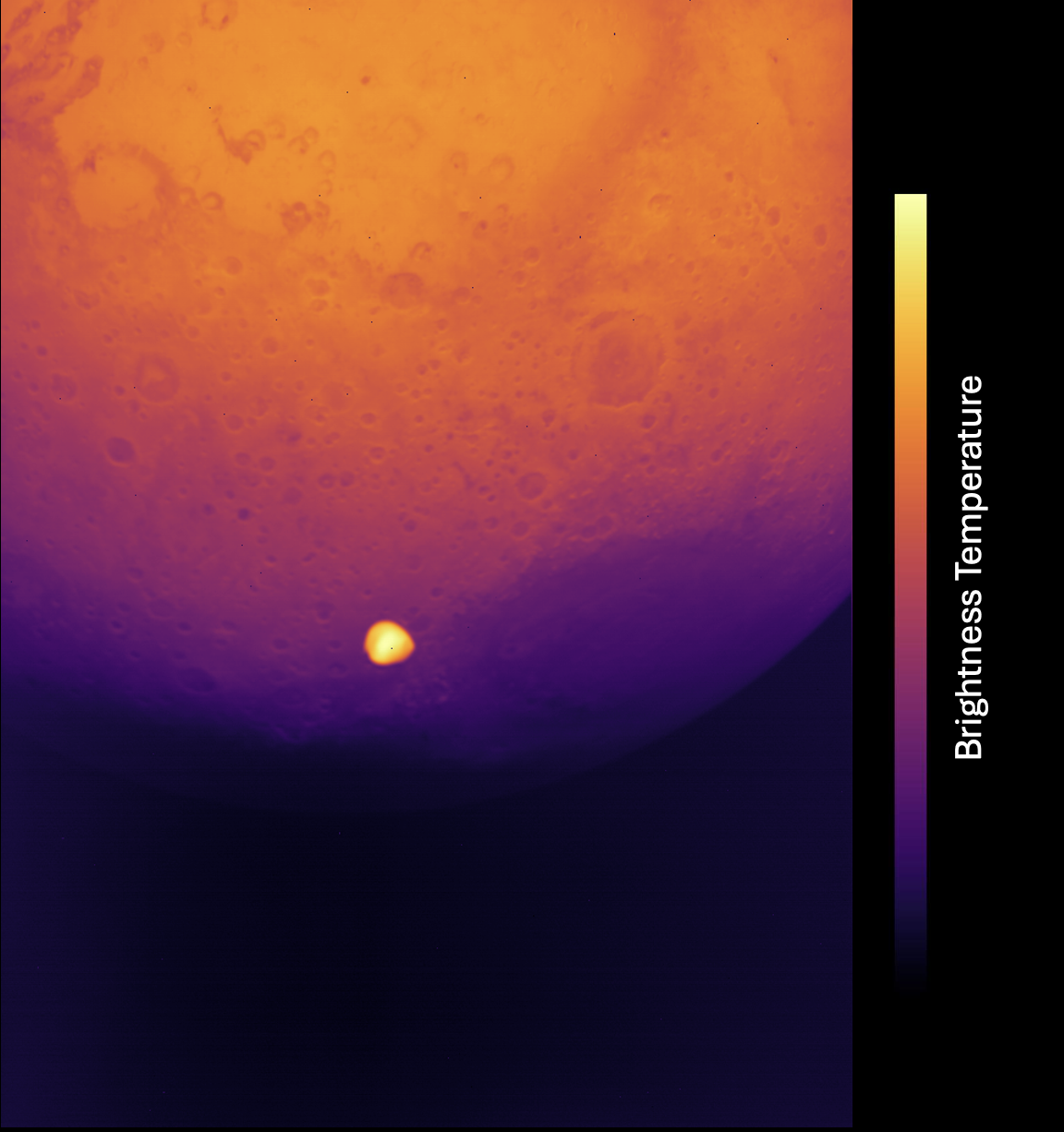

Another instrument on Hera that could reveal clues about Deimos’ birth is its Thermal Infrared Imager. Developed for the mission by the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), its purpose is the mapping of temperatures on the surfaces of celestial bodies such as Mars, Deimos, or Didymos and Dimorphos.

“The purpose of these temperature measurements is to find out the compaction state of the material; is it really fluffy, fine-grained stuff, or is it dense, coarse material?” said JAXA’s Seiji Sujita, of the University of Tokyo, during the webcast. “When we analyze the data in the coming days and weeks, we will probably be able to tell the difference between the grain sizes, and that’s probably going to tell us something about the origin of Deimos.”

Of course, Mars is not the end goal of Hera. Its primary mission is to visit the binary asteroid Didymos and Dimorphos, the latter of which was struck in 2022 by NASA’s DART (Double Asteroid Redirection Test) spacecraft, which collided with Dimorphos and altered the smaller asteroid’s orbit around Didymos in an experiment to test whether we could nudge aside an asteroid on a collision course with Earth. Hera is heading there to study the crater made by the DART impact, and to learn more about the properties of both asteroids.

Having launched in October 2024 atop a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, Hera is intended to reach Didymos and Dimorphos by the end of 2026. To get there faster and using as little propellant as possible, Hera has flown to Mars for a gravitational slingshot.

“Mars was at exactly the right spot for us to get to Didymos and save propellant,” said Carnelli. “So we literally used the gravity of Mars to pull us and then throw us deeper into space by harvesting a bit of the planet’s energy.”

But to fly past Mars in such a way that Hera got to see Deimos too required some gentle persuasion of ESA’s Flight Dynamics team.

“I really appreciate the team because the main objective of this fly-by was to put Hera on the correct trajectory with Didymos in 2026, but we asked if they could make a flyby of Deimos and they accepted, but it was a challenge because they had to change Hera’s trajectory to do so.”

The next step, besides analyzing the data collected from Mars and Deimos, is preparing for rendezvous with Didymos and Dimorphos. This is the job of Hera’s operations team, who will initiate the ‘asteroid proximity operation’

“That’s going to be a real challenge — just imagine flying through an environment that’s so dynamic,” said Carnelli. Hera will enter into the double asteroid system and orbit Didymos, but it has to deal with not only Didymos’s gravity but also neighbouring Dimorphos, which has an average distance from Didymos of just 3,780 feet (1,152 meters), and the constant motion of Dimorphos around Didymos.

“I dream of flying between the two asteroids and being very close [to them] and doing things we never imagined before,” said Carnelli. “We’re really writing a page of space history here.”