Conny Waters – AncientPages.com – Some years ago, archaeologist Walter Crist came across a notable limestone slab in the collection of the Thermenmuseum, now known as the Roman Museum.

This worked stone, measuring 21 by 14.5 centimeters, was originally discovered in Heerlen during the late 19th or early 20th century. Heerlen was historically significant as the Roman settlement of Coriovallum. As a specialist in ancient games, Crist found the artifact particularly intriguing upon its discovery.

What Does The Stone Reveal?

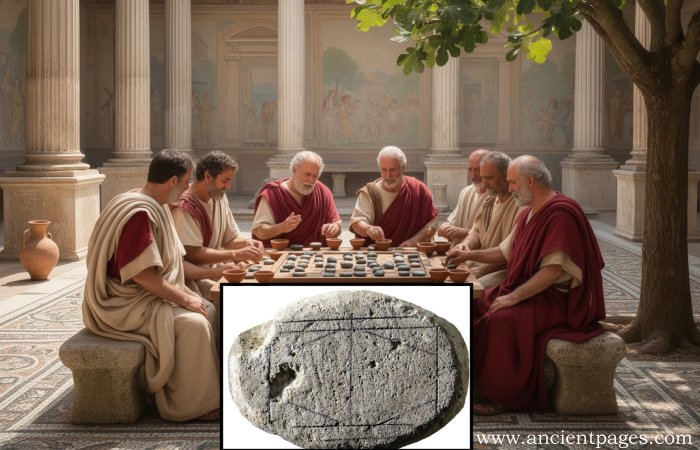

“The stone’s appearance, together with the wear, strongly suggested a game, but I didn’t recognize the pattern from other ancient games I know.” The piece of limestone shows a rectangle containing four diagonal lines and one straight line.

The stone with the carved pattern. Credit: Leiden University

“The scans make the traces on the stone much clearer,” Crist explains in a press release. “Some of those traces are a fraction of a millimeter deeper than others, meaning they were used more intensively. We also see that the edges of the stone are neatly finished, which indicates that this is a finished product and not a stone that still needs further working.” The stone was worked an estimated 1,500 to 1,700 years ago.

A Game Played Much Earlier Than Prevously Thought

Researchers from Dutch, Belgian, and Australian institutions have used AI to reconstruct the rules of a board game that was carved into a stone discovered by Walter Crist in Heerlen, Netherlands, in 2020. Their findings indicate that this type of game was played several centuries earlier than previously believed.

3D scan of the stone. Credit: Leiden University

Researchers carried out an experiment where two AI agents competed using a stone as the game board, following rules inspired by ancient European board games. Their analysis revealed that the wear patterns on the stone are most consistent with blocking games—games in which players try to prevent their opponents from making moves.

Blocking games have only been documented since the Middle Ages, so this finding is particularly significant. According to Crist, the study offers evidence that board gaming took place during Roman times, indicating that such games were played several centuries earlier than previously thought.

See also: More Archaeology News

“Research on ancient games depends on the identification of repeating patterns of board geometry and on the ability to connect objects found in the archaeological record to games named or depicted in art. The potential to misidentify singular examples is therefore great. Yet the materiality of play is often ephemeral and isolated examples of particular games that people were inspired, on occasion, to make into lasting objects are perhaps more common than they appear to be.

By combining AI simulation with use-wear analysis to identify and model traces of game play, it is possible to not only identify potential game boards, but also to rebuild playable rulesets that may provide indications regarding the ways that people played games in the past. The ability to identify play and games in archaeology strengthens the understanding of our ludic heritage, and makes ancient life more accessible to people in the present, as the act of playing a board game is fundamentally the same today as it was in past millennia,” the researchers write in their study.

The new approach may also lead to further discoveries. “This is the first time that AI-driven simulated play has been combined with archaeological methods to identify a board game,” Crist says. “This research provides archaeologists with additional tools to identify games from ancient cultures.”

The study was published in the journal Antiquity

Written by Conny Waters – AncientPages.com Staff Writer