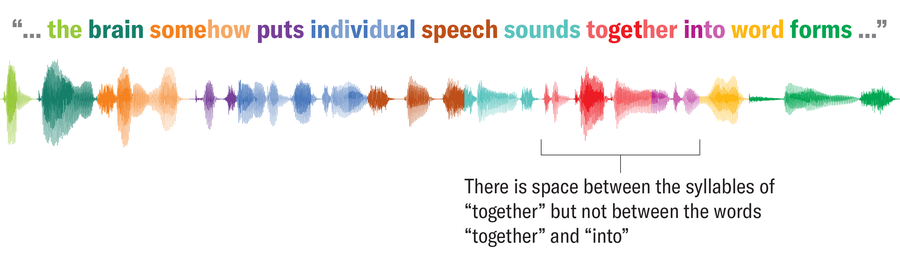

Speech sounds like it is made of words, but that impression has more to do with what’s in our heads than with what comes out of our mouths. In natural speech, there are no clear acoustic boundaries separating words; we pause about as many times within words as we do between them. This is especially evident when listening to an unfamiliar language being spoken: words often seem to “blur” together into one smeared stream of sound.

So how does the brain slice speech into recognizable chunks? Recent research by neurologist and neurosurgeon Edward Chang of the University of California, San Francisco, and his colleagues reveals a hint. In one study, published in Neuron, the researchers looked at fast brain waves that flicker about 70 to 150 times per second through a part of the brain involved in speech perception. They realized that the power of these “high-gamma” waves consistently plummets about 100 milliseconds after a word boundary. Like a blank space in printed text, the sharp drop marks the end of a word for people who are fluent in that language.

“To my knowledge, this is the first time that we have a direct neural brain correlate of words,” Chang says. “That’s a big deal.”

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In a different study, published in Nature, the scientists reported that native speakers of English, Spanish or Mandarin all showed these high-gamma responses to their mother tongues, but listening to foreign speech didn’t trigger the dips as strongly or consistently. Bilingual people showed nativelike patterns in both their languages, and the brain activity of adult English learners listening to English looked more nativelike the more proficient they were.

Source: “Human Cortical Dynamics of Auditory Word Form Encoding,” by Yizhen Zhang et al., in Neuron, Vol. 114; January 7, 2026; styled by Amanda Montañez

“This is a great first foray into the question” of how the brain marks word boundaries, says Massachusetts Institute of Technology neuroscientist Evelina Fedorenko, who wasn’t involved in either work. She adds, however, that it’s not yet clear whether actually understanding a language is necessary for word-break recognition. Maybe the brain simply picks up on sound patterns it hears often, regardless of comprehension. Or maybe meaning matters, as with muffled speech in a movie that suddenly sounds clearer when subtitles are switched on. Even if speech sounds and higher-level language structures are processed differently in the brain, the two can feed back into each other. Experiments with artificial language that mimics natural speech sounds could tease apart the details, Fedorenko says.

When it comes to deciphering words, Chang suspects there may be no clean distinction between these different types of processing; the signal he and his co-workers linked to word boundaries occurs in a brain region that also recognizes speech sounds. Historically, Chang says, researchers imagined that different levels of structure in language, from sounds to words up to meaning, would be processed in dedicated brain regions. These new findings, he adds, “kind of blow that out of the water. This is actually all happening in the same place. When we compute sounds, we are computing words.”

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.