Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com – Did you know that ancient peoples might owe their survival instincts to our extinct hominin ancestors? Recent studies suggest that genetic material from these early hominins played a vital role in helping ancient populations adapt to the diverse and challenging environments of the Americas.

Thousands of years ago, ancient humans embarked on a perilous journey across the Bering Strait, traversing hundreds of miles of ice to reach the uncharted territories of the Americas. A new study conducted by researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder reveals that these nomadic travelers carried an unexpected genetic inheritance—a segment of DNA from an extinct hominin species. This genetic legacy may have played a crucial role in helping early humans adapt to the environmental challenges they encountered in their new surroundings.

Denisovans – An Ancient Species Related To Humans

“In terms of evolution, this is an incredible leap,” said Fernando Villanea, one of two lead authors of the study and an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology at CU Boulder. “It shows an amount of adaptation and resilience within a population that is simply amazing.”

The research offers new insights into Denisovans, an ancient species related to humans. These hominins occupied areas ranging from modern-day Russia to Oceania and westward to the Tibetan Plateau. Despite their extinction tens of thousands of years ago, much about Denisovans is still not well understood. Scientists first identified this species 15 years ago through DNA analysis of a bone fragment found in a Siberian cave. Like Neanderthals, Denisovans may have had prominent brows and lacked chins.

“We know more about their genomes and how their body chemistry behaves than we do about what they looked like,” Villanea said.

A Little-Known Gene

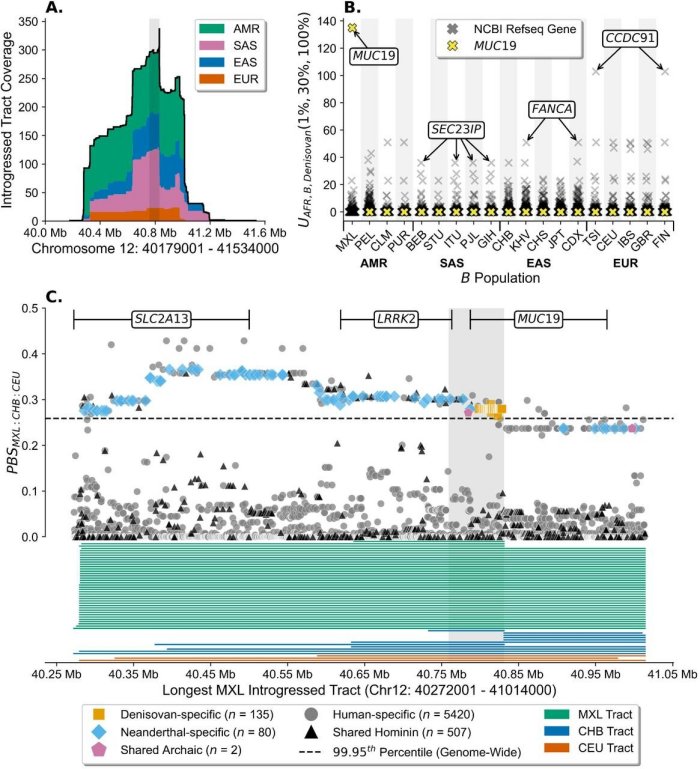

A substantial amount of research indicates that Denisovans interbred with both Neanderthals and modern humans, significantly influencing the genetic makeup of contemporary populations. To investigate these connections, Villanea and his team, including co-lead author David Peede from Brown University, analyzed the genomes of individuals worldwide. Their focus was on a gene called MUC19, which is crucial for immune system function.

The study found that individuals with Indigenous American ancestry are more likely than other groups to possess a variant of this gene inherited from Denisovans. This ancient genetic contribution may have played a crucial role in helping humans adapt to the diverse environments encountered in North and South America.

“It seems like MUC19 has a lot of functional consequences for health, but we’re only starting to understand these genes,” he said.

Previous research has demonstrated that Denisovans possessed a distinct variant of the MUC19 gene, characterized by a unique series of mutations, which they transmitted to certain human populations. Such genetic mixing was prevalent in ancient times; today, most humans have some Neanderthal DNA, while Denisovan DNA constitutes up to 5% of the genomes of individuals from Papua New Guinea.

In their current study, Villanea and colleagues aimed to explore how these genetic legacies influence our evolutionary trajectory. They examined existing genomic data from modern humans in Mexico, Peru, Puerto Rico, and Colombia—regions with significant Indigenous American ancestry and DNA.

Their findings revealed that one-third of people with Mexican ancestry carry the Denisovan variant of MUC19 within segments of their genome linked to Indigenous American heritage. This contrasts sharply with individuals of Central European descent, where only 1% possess this variant.

Moreover, the researchers uncovered an intriguing discovery: in humans carrying this Denisovan gene variant, it appears surrounded by Neanderthal DNA.

Previous research has demonstrated that Denisovans possessed a distinct variant of the MUC19 gene, characterized by a unique series of mutations, which they transmitted to certain human populations. Such genetic mixing was prevalent in ancient times; today, most humans have some Neanderthal DNA, while Denisovan DNA constitutes up to 5% of the genomes of individuals from Papua New Guinea.

In their current study, Villanea and colleagues aimed to explore how these genetic legacies influence our evolutionary trajectory. They examined existing genomic data from modern humans in Mexico, Peru, Puerto Rico, and Colombia—regions with significant Indigenous American ancestry and DNA.

Their findings revealed that one-third of people with Mexican ancestry carry the Denisovan variant of MUC19 within segments of their genome linked to Indigenous American heritage. This contrasts sharply with individuals of Central European descent, where only 1% possess this variant.

Moreover, the researchers uncovered an intriguing discovery: in humans carrying this Denisovan gene variant, it appears surrounded by Neanderthal DNA.

A New World

Villanea and his team propose an intriguing sequence of events: Before humans traversed the Bering Strait, Denisovans interbred with Neanderthals, transferring the Denisovan MUC19 gene to their descendants. Subsequently, Neanderthals mated with humans, passing along some Denisovan DNA. This marks the first instance scientists have identified of DNA transferring from Denisovans to Neanderthals and then to humans. As humans migrated to the Americas, natural selection favored the proliferation of this inherited MUC19 variant.

Signals of adaptive introgression at MUC19. Credit: Fernando A. Villanea et al

The reason why this Denisovan variant became prevalent in North and South America but not elsewhere remains uncertain. Villanea suggests that early inhabitants of the Americas faced unique conditions unprecedented in human history, such as novel foods and diseases. The presence of Denisovan DNA might have provided them with additional advantages in adapting to these challenges.

“All of a sudden, people had to find new ways to hunt, new ways to farm, and they developed really cool technology in response to those challenges,” he said. “But, over 20,000 years, their bodies were also adapting at a biological level.”

See also: More Archaeology News

To build that picture, the anthropologist is planning to study how different MUC19 gene variants affect the health of humans living today. For now, Villanea said the study is a testament to the power of human evolution.

“What Indigenous American populations did was really incredible,” Villanea said. “They went from a common ancestor living around the Bering Strait to adapting biologically and culturally to this new continent that has every single type of biome in the world.”

The study was published in the journal Science

Written by Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com Staff Writer