If there is one phrase I have detested all my life, it is talk of the ‘Phoney War’ – the months between September 1939 and June 1940 when, in popular thought, hardly anyone in Britain’s forces paid the supreme sacrifice.

And one thing I have done my best to avoid, since I lost my father in May 2023, is a local Lewis funeral, complete with chafing, essential rites.

Viewing the remains, processing the coffin, taking your turn to carry it, another turn with a shovel and not departing till said grave be filled and a Swiss roll of grassy sod has been unfurled atop it.

It’s raw, real, tough, and – in its own way – healing; in the old Alcoholics Anonymous proverb, the best way of negotiating any strong emotion is through it, not around it.

Till Thursday last, I desperately limited outings for manly handshakes, the squeeze of a widow’s hand and the ghastly drumming sound as I flung yet more sandy soil on an uncushioned coffin lid six foot under.

But then, that Thursday, both fierce impulses hopelessly collided.

I have sadly few memories of my Marybank neighbour, Alex Dan Nicolson. A kindly man who would hail me on the road and once rejoiced to bump into Daddy, his old Laxdale schoolfellow, if a couple of years behind.

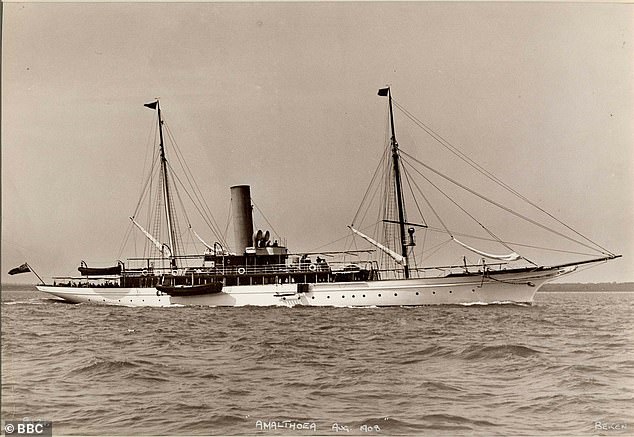

HMS Iolaire sank on New Year’s Day, 1919, with the loss of some 200 returning veterans

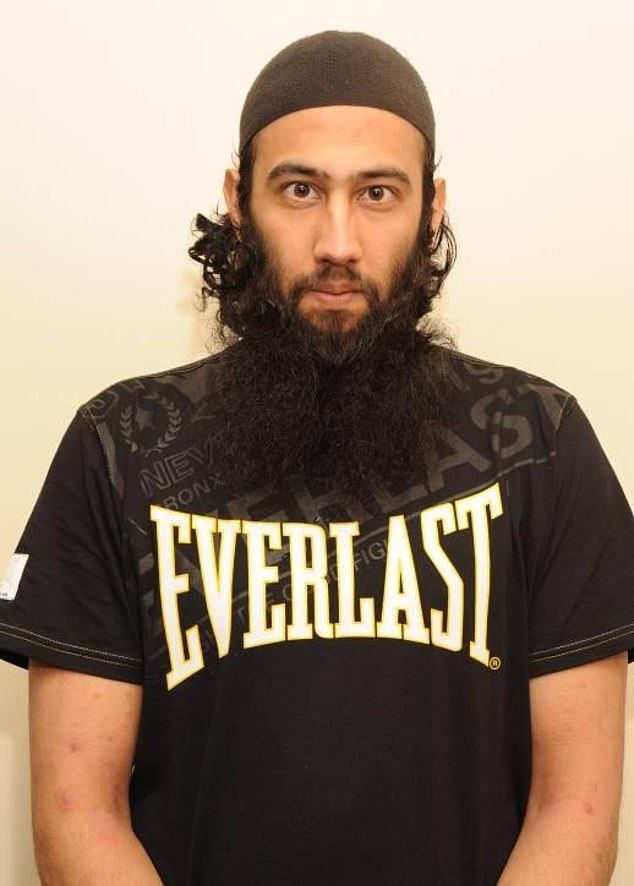

Alex Dan, 87, had been out of circulation for a long time, though till the last – collapsing, the other Sabbath, by his devoted wife of 65 years – he retained a vital wi-fi signal with a beloved 22-year-old grandson, who coaxed forth chuckles to the end.

There is even a recent photo of three generations – Alex Dan, his son John Murdo and grandson Sam – where mutual regard is evident: Alex Dan not knowing quite where and when, but aware he was with close kin who loved him.

He had no memory whatever of his own father: lost, on November 23, 1939, with HMS Rawalpindi.

Having hit hailing distance of my 60th birthday wondering if, ahem, I was blessed with an eternal father, I cannot imagine what that must have felt like for a little 1940s boy in an island so knee-deep in orphans of both German wars that sympathy would have been scant indeed.

Lewis knew no ‘Phoney War’. Something between a quarter and a third of the entire Royal Naval Reserve, in September 1939, were from this island.

So esteemed for their pluck, self-discipline, seamanship and dignity there are tales of captains at Plymouth, Portsmouth, Harwich and Rosyth and the rest hitting quaysides hailing mustered reservists, ‘I want Stornoway men… any Stornoway men?’

My MacLeod grandfather was one of them.

His widow, who survived him by a decade, could never touch on the memory of one lad from her own Lewis township – among Britain’s earliest casualties in Hitler’s war – without melting in tears.

One man carrying a rope managed to swim ashore from the stricken Iolaire, allowing some veterans to make it to safety

She composed a song for him, as Lewismen drowned in their hundreds before Churchill even made Prime Minister.

And – in defiance of cultural child-naming rules at the time – even named her firstborn son after his father. To her last days she never forgot the terror, infant daughter in her arms as her man at scant 1939 notice strode away at Govan call-up, unsure they would ever embrace again.

Said baby girl would be dead by July 1940, a suffocating unfixable fact my father, born that November, would bear all his days.

Daddy should have been an Angus, not a Donald, but Granny had little hope her man would survive the war, might even have fretted some grandson would fetch up writing stuff like this in German.

My grandfather survived the war. Oddly, he could freely discuss the 1919 Iolaire disaster with his grandchildren – when near two hundred returning Lewis veterans of the Great War were drowned on their Stornoway doorstep by Admiralty incompetence.

‘Cart after cart after cart,’ he murmured when I was a child of ten, ‘cart after cart, every cart passing our house with coffins…’

He was, in contrast, all but incapable of discussing the tragedy with his offspring.

Yet his own 1939-45 service he could only discuss with them. What brain wiring did that reflect?

I never managed – he died in 1986 – to draw him out much on it. I do know that, from naval-rating ranks, he made Chief Petty Officer, which suggests some smarts, and – thanks to Daddy – that he had terrified memories of being a ‘powder monkey’.

Likely the term goes back to Henry VIII; the job was to load shells into guns. In externally bolted, pivoting gun turrets.

In certain knowledge that, were HMS Doomsday sunk, you would join Davey Jones’s Locker with her.

In happier experience, my grandfather served in HMS Glasgow in determined pursuit of the Bismarck.

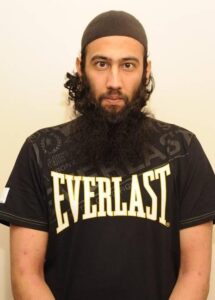

A lex Dan Nicolson had no such memories; no paternal knee to lean by or a father’s caress through his hair.

He was just another little boy, ambling through the village in shorts, who had lost his Da in the war and without even memory of his smile, his touch, his voice or his scent.

And – Constant Reader, you might remember – scant weeks ago he lost his best Marybank friend: his schoolfellow, my next-door neighbour Al MacDonald.

Though latterly too frail to pad the hundred yards down the road for a visit, ‘Titch’ phoned Alex Dan to the end.

In Aignish cemetery last week, and in a biting eastern wind, their last township contemporary – ‘Murdo Lava,’ as we call him – was in determined attendance.

Remarkably, three strapping descendants – a son, grandson, a willowy great-grandson fond of fly-fishing – are in full-time jobs as Murdo Lava still strims his own grass.

Hitler’s war cast a huge shadow upon my generation. It had ended but two decades before my birth. My schoolmasters included many men who had served in it.

My mother, for as long as I can remember, has breathed in horror of the Holocaust; thousands and thousands of her small European contemporaries were murdered in it – and grandparental horror at any waste of food haunts me still.

But Hitler’s war has long poured over the sill of our collective memory: not two hundred Scottish veterans still survive and, no doubt, not a few in desperation to enlist lied about their age.

She and my father had their memories, nevertheless; Alex Dan, up the road, we laid to rest without the recollections he longed for most of all – of a Da whose only known grave is the sea.

The retiring collection at the funeral, Thursday last, was for the RNLI; the last item of praise was Nearer My God To Thee – and that whispers everything.