There are two books on opposite sides of Ben Proud’s living room in Dubai. One is a business manifesto titled Principles and the other is The Buddha Teachings, and together they lurk as silent witnesses as a sporting pariah discusses his chosen path.

Try as he might to avoid it, Proud knows the gist of what folk say about him now. He also knows there is no way back, not since he cashed in with the Enhanced Games and their realisation of an age-old hypothetical: how fast might these guys go if…

We are talking about his decision to become that guy. The kind he despised as a multiple world champion of swimming and the winner of an Olympic silver medal for Team GB.

So, as we go deep into the second hour of this interview, Proud is imagining how he will feel in the very near future, assuming he goes through with his intention to infuse himself with performance-enhancing drugs. He leaves a long pause before sharing the thought.

‘It’s going to be like stepping through a veil and you can no longer step back,’ he tells me. ‘I will no longer have the ability to say, “I’ve been drug-free my entire life”. Yeah, that’s going to be a tricky night. A lot of conversations with myself.’

Proud falls into another silence. There have been a few of those in the past four months, since he crossed over, and there will be more before May, when he is due in Las Vegas for a 50m freestyle race against three other pariahs.

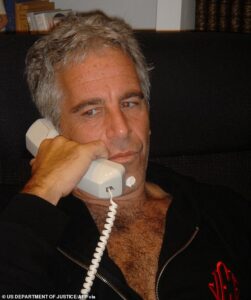

Former Great Britain swimmer Ben Proud at his home in Dubai. Proud will compete at the Enhanced Games in Las Vegas in May

Proud in his Team GB days, celebrating winning a silver medal in the 50m freestyle at the Paris Olympics in 2024

If he wins in Vegas, he will get $250,000. Last place would land him $50,000, which is five times what he received for any one of his three world titles, and then there’s the biggie – a $1million bonus for breaking the world record on top of a six-figure signing fee. By his description, even the worst-case yield is a ‘financial metamorphosis’ in his life. That’s his reason.

But it’s doping. And Proud hated dopers. So do his closest friends in swimming, Tom Dean and Duncan Scott, five Olympic golds between them. And now he’s about to become a version of the thing they collectively loathed; a man who in this conversation will discuss testosterone as a substance of choice, and in proximity will talk about health risks and the pain of being told by a swimmer’s mother that he let down her son.

It’s complicated. Indeed, there aren’t enough pages in those books to find a zen state from this kind of business decision. But even if people don’t understand, he wants to explain why he regrets nothing.

Proud is an intelligent man of 31. Articulate, warm and polite. ‘A bit of a sensitive soul,’ as he puts it. Since it was announced in September that he was the first British athlete to join the Enhanced Games, that sensitivity has been tested. The traditional sporting world has mostly ostracised him.

‘I’ve tried to shield myself from the reaction,’ he says. ‘There are people writing on message boards or wherever to say, “Drugs cheat, cheated his whole life etc”, which I never did, and there are some who are probably curious to see what happens. I heard Matt Damon and Ben Affleck talking about it the other day.

‘The harder parts have been the conversations with people I am close to. Not so much family. But some of those conversations with people in swimming who I care about have been difficult.’

Proud’s mind goes back to last autumn, before his decision became public. By then, he had spent a couple of years deliberating over a concept that had first been unveiled to great outrage in June 2023. My reporting included.

But Proud was intrigued from the start – he admits to me that the first overtures came from his side, intrigued to know what might be on offer for an athlete with little cash saved after 10 years in elite sport. In August of 2025, days after winning silver at the world championships in Singapore, he signed. That’s when he started ringing around his closest colleagues in swimming.

Proud was intrigued from the start – he admits that the first overtures came from his side, intrigued to know what might be on offer for an athlete with little cash saved after 10 years in elite sport

‘I’ve not had anyone shout, “Shame on you” to my face, but I was scared about telling the guys on the British swimming team,’ says Proud

‘I’ve not had anyone shout, “Shame on you” to my face, but I was scared about telling the guys on the British swimming team,’ Proud says. ‘To be honest, the ones I value most have been supportive. I think my biggest fear was telling Duncan Scott and Tom Dean, who were always really good friends.’

It was Scott who staged a laudable podium protest at the world championships in 2019, by refusing to stand next to China’s Sun Yang, who had previously served a doping ban. ‘Telling Duncan and Tom, it was like, “This is what’s happening, I don’t think I can turn it down”. They’ve been supportive, not of Enhanced, but of what it means in my life, I think.’

I ask if the three of them still talk regularly and there’s another hesitation. ‘Not so much since I signed,’ says Proud. ‘Obviously I am not seeing them at the pool and I don’t think we can really be seen hanging out together any more. It is going to have an effect on the relationship but we vowed to stay friends.

‘The hardest person to tell was actually James Gibson (a British world champion-turned-coach), who was basically my mentor for about seven years. He wasn’t angry, and that’s what makes it worse, because you know you’ve made someone upset on the deeper side. My hope is that in time people can understand my reasoning.’

It’s an ambitious hope. But that becomes a conversation about finance, which in turn is an examination of the wider Olympic system.

There are misconceptions about the value of a medal and Proud has plenty of them – between 2014 and 2024, he won two golds in world championships, six European titles, and five at the Commonwealth Games. Then there was the Paris Olympics, in 2024, where he won silver.

‘I’m not going to paint myself as a victim because I wasn’t,’ he says. ‘But people have an idea of an Olympic medallist leading a certain life that isn’t accurate.

‘I got huge pride from that Olympic medal but there was no financial avenue, other than securing your UK Sport (lottery) funding for another 12 months. That is around £28,000 a year, and it’s a great help, but in my 10 years it never increased with inflation.

Team GB’s Duncan Scott stages a laudable podium protest at the world championships in 2019, refusing to stand next to China’s Sun Yang, who had previously served a doping ban

‘Prize money in swimming isn’t what it is in some sports,’ says Proud. ‘The performance lifestyle is very, very hard and the reality is you have to earn a living’

‘When I was 20, 21, life was great with that funding. But prize money in swimming isn’t what it is in some sports. There is something amazing about chasing a dream, but that performance lifestyle is very, very hard and the reality is you have to earn a living. You still want to have something when you stop.

‘My average (annual) earnings across my career were about £50,000. One year I got to around £100,000, so I probably had more than a lot of athletes, but there are big deductions. I was always outside the main British system, training my own way, so I was often paying for my camps, physio, nutrition, travel.

‘I’d be lucky if I could invest into my ISA account for one or two years of my career. Many years would be the opposite. I remember going into the Tokyo Olympics (in 2021) and I was several thousand pounds in debt.

‘After 10 years, it comes to the point when you need more. I want to be able to support my mum later into her life, and eventually if there’s kids or marriage, I’d like to provide a good life, and how do you do that?’

The Enhanced Games has zeroed in on that dilemma. Even if we loathe their vehicle, most would not dispute the inequity within the status quo – the International Olympic Committee generated a reported surplus of around £910m in 2024 and its star performers got the thinnest end of the wedge. Proud’s disillusionment is at least understandable.

‘This would not have happened if that was handled correctly,’ is part of his summary.

But it is a vulnerable argument when we broaden it out. Because can the flaws of one system ever justify an athlete joining an organisation that incentivises the use of banned substances?

At best, the Enhanced Games concept ought to be viewed as a controlled experiment conducted far outside our definitions of sport. At worst, it could normalise and advertise drugs that are dangerous in the wrong hands and might sway those deliberating an edge in the conventional sphere.

Around 20 athletes of a targeted 50 have signed up for the Enhanced Games so far, including the British sprinter Reece Prescod, pictured here (centre back) after winning 4x100m relay bronze at the World Championships in 2022

Prescod claims he won’t take any performance enhancing drugs during the Games

For his part, Proud is comfortable. ‘I don’t regret my decision,’ he says. ‘If you put me on stage in front of a bunch of swimmers’ mums, then I’ll probably feel embarrassed or ashamed. The hard bit was a mum saying to me on Instagram, “My son admired you”.

‘As a gut feeling, that sucks. But this will multiply by five the money I have. It gives me choices in my life that I never had. If you go outside and there’s a winning lottery ticket on the floor, would you pick it up? To me it was a no-brainer to take it.’

Proud adds: ‘I want to do what is right for me and then go back into my small bubble with my girlfriend, my family, my friends, my coffee. My only regret is if I’ve hurt people, but I’ve had to be selfish and shield from what is said outside.’

As it happens, this is one of those days when words are being spoken out there – when I leave the interview, a notification arrives from UK Sport to say Proud has brought swimming into disrepute and is no longer eligible for financial assistance. They are closing the stable door long after the horse has bolted.

Proud has been through the why and we have moved on to the how and what.

Around 20 athletes of a targeted 50 have signed up for the Enhanced Games so far, including the British sprinter Reece Prescod, and each has been presented a choice: use drugs that are banned in sport but approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, or take none at all.

Prescod, for one, claims that he won’t, and the decision for all of them will be finalised imminently after screening in Abu Dhabi. ‘It will be extensive,’ says Proud. ‘It will be a three-day check on your health, your fertility, organs and areas where you might respond best.’

Proud’s decision to dope has not been formalised, but he is leaning that way. ‘If I end up taking something, the reason will be ultimately to get the best out of this contract,’ he says. ‘I’m never going to compete in the Olympics or the worlds again, and that leaves you with a question, “Well, why wouldn’t I take what’s available?”’

Proud says there are seven doctors he has liaised with on the aspect of taking drugs and feels ‘very safe’, but it is still a leap of faith

Brazil’s Cesar Cielo has held the world record of 20.91sec for the 50m freestyle for 17 years. Cielo once failed a drugs test

There are powerful answers to Proud’s question and they point to history – the past is littered with athletes who suffered awful consequences from using banned drugs.

Predictably, the Enhanced Games have talked up the supervision of their core element. Proud says there are seven doctors he has liaised with on this aspect and feels ‘very safe’, but it is still a leap of faith. It is still the variable that he says caused his brother a few ‘sleepless nights’.

What follows is the kind of on-record exchange rarely held with an active athlete, if ever.

‘Testosterone, from what I’ve read, has the most green flags in terms of power output, lean muscle mass,’ Proud says.

What about human growth hormone, I ask? ‘That gives more enlargement, which I don’t need. My discipline is more skill-based so it is not something I am interested in and has a different health risk factor.’

And EPO, the distance-runner’s choice? ‘That is an interesting one for training capacity. The benefits around recovery will be large.’

It is a surreal conversation. It is for Proud, too. Earlier, he had told me: ‘For 15 years of my life, I was completely anti-drugs. I hated the thought of cheats. And now I’m considering taking these substances. It’s not cheating because it’s inside the rules, but it’s a very different mind shift.’

Even factoring for the problems of the traditional Olympics, where the notion of clean sport is routinely exposed as a fantasy, the Enhanced Games is a scenario without precedent. It remains to be seen what will come of their gathering in Vegas, a backdrop that feels strangely appropriate.

‘Testosterone, from what I’ve read, has the most green flags in terms of power output, lean muscle mass,’ Proud says

And EPO, the distance-runner’s choice? ‘That is an interesting one for training capacity,’ Proud says. ‘The benefits around recovery will be large’

The Enhanced Games’s backers, including the billionaire Peter Thiel and Donald Trump Jr, have plainly seen vast investment potential at the intersection of the pharmaceutical industry and provocative content. Cast as data points in a clinical trial, the athletes will effectively serve as billboards for the substances they use and frontier-messaging around living a longer life.

Like Proud, they have been paid well to do so. Like Proud, they have concluded the criticisms are an acceptable loss for the returns.

Will he break the record and get the big prize? It currently stands at 20.91sec and has been held for 17 years by Cesar Cielo of Brazil. That Cielo once failed a drugs test is possibly a reason to caution against excessive sanctimony. Or maybe that is an obscene piece of equivocation. Either way, free will is free will and Proud has exercised his.

With it, he says he would be ‘confident’ of finding $1m on the other side of that veil, if he takes the step. Time will tell if it is worth the cost.