Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com – Our understanding of ancient literature is mainly due to the diligent work of scribes. The survival of works by Aristotle, Galen, and Ptolemy can be attributed to generations of copyists who painstakingly reproduced these texts by hand.

However, the process of copying was not always straightforward. Scribes often made edits during transcription—resolving contradictions, adding interpretations, merging readings from various sources, and occasionally making errors. Over time, these minor changes accumulated.

Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai, Egypt. Credit: Berthold Werner – CC BY-SA 3.0

To trace the evolution of a text, modern researchers employ a method known as a stemma—a reconstructed family tree of manuscripts. This tool not only helps approximate the earliest recoverable version of a text but also sheds light on how it was read, reshaped, and reimagined over centuries and across different cultures. The larger the textual tradition, the more complex this task becomes; for instance, the New Testament Bible represents one of the most intricate traditions that have endured through time.

Thousands of manuscripts remain in their original Greek language, with many more available in translations such as Latin, Syriac, and Arabic. Each version exhibits its own unique variations. Recent estimates indicate that the New Testament manuscript tradition contains approximately half a million textual variants, averaging three or four for each word. Given the complexity and volume of this data, traditional methods have limitations in tracing these variations. Consequently, scholars are now utilizing tools from other fields to advance their research.

The Genetics Of Texts

One particularly effective tool is phylogenetics—a method originally developed by biologists to study evolutionary relationships by examining how traits are inherited and change over time. This approach is now being applied to unravel the history of texts. During the COVID-19 pandemic, scientists used similar techniques to track the virus’s spread by analyzing mutations in its RNA. The same methodology can be employed for manuscripts; just as geneticists reconstruct transmission histories through genetic changes, textual scholars can trace a text’s evolution by comparing its variants.

Textual scholars have used phylogenetics to study manuscript traditions for the likes of the Norse poem, Gróagaldr. Picture: W.G. Collingwood/Wikimedia

Biologist Richard Dawkins highlighted this parallel: “So similar are the techniques and difficulties in DNA evolution and literary text evolution that each can be used to illustrate the other.”

How A Norse Poem Changed Biblical Studies

In the 1980s, Peter Robinson completed his PhD focusing on Old Norse manuscripts. In 1991, he issued a challenge on a network bulletin board: could someone replicate his analysis using computational methods?

Specifically, he sought to recreate the table of relationships for approximately 44 different manuscripts of the Old Norse narrative ‘Svipdagsmál’ using purely statistical or numerical techniques—a task he had previously accomplished through external evidence and traditional stemmatic methods.

Biologist Robert O’Hara responded with a phylogenetic approach and remarkably replicated Robinson’s months-long manual work in just five minutes. Since this breakthrough, textual scholars have applied phylogenetics to explore manuscript traditions ranging from The Canterbury Tales to the New Testament.

In the book “Codex Sinaiticus Arabicus and Its Family,” Dr. Robert Turnbull examines how advanced phylogenetic techniques from biology can be applied to trace the history of New Testament Gospel manuscripts. Biologists understand that genetic mutations do not occur at a uniform rate, and Dr. Turnbull leveraged this concept to analyze manuscript traditions, enabling his model to differentiate between various types of textual changes.

This distinction is crucial because minor alterations that do not impact meaning are more common, whereas significant changes are rarer. By modeling these rates separately, researchers can now estimate the frequency with which scribes introduced specific kinds of changes, thereby reconstructing the text’s evolution with enhanced precision.

These modifications range from small spelling adjustments or word substitutions using synonyms to more substantial alterations such as adding or omitting entire sentences or paragraphs.

In 1975, a long-forgotten storeroom was uncovered at St. Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai Peninsula—one of the oldest Christian monasteries globally, located deep in Egypt’s wilderness. This discovery included hundreds of previously unknown manuscripts in Greek, Arabic, Syriac, and other languages. Among these was an extraordinary find: a neglected Arabic translation of the Gospels derived from a Greek source.

“I’ve traced the history of this translation and pieced together its story from the surviving manuscripts.

What makes this translation so striking is its preservation of hundreds of rare textual readings – subtle differences that shed light on how the Gospels were copied and transmitted.

One important example comes from the very first verse of the Gospel of Mark.

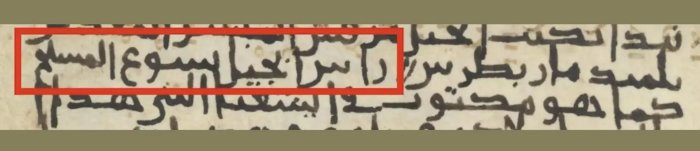

Most biblical manuscripts begin: “The beginning of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God”.

But in a small number – including this Arabic translation – the words “Son of God” are missing.

It may seem like a small omission, but it’s one that raises big questions about how early Christian communities understood Jesus – and how their texts evolved over time,” Dr. Turnbull said in a press release.

A Place In The Gospel Tree

To place this Arabic translation within the broader manuscript tradition, Dr. Turnbull developed a dataset of its variant readings and incorporated it into a phylogenetic analysis alongside hundreds of other Gospel manuscripts and translations. Utilizing a supercomputer at the University of Melbourne, the model assessed millions of potential relationships among these texts, determining their likelihood based on shared variation patterns.

In the opening verse of the Arabic translation of Mark’s Gospel, the words ‘Son of God’ are missing. Picture: St. Catherine’s Monastery

The outcome was a textual family tree that provided the most plausible explanation for the evidence and indicated our confidence in this reconstruction. The analysis revealed that this Arabic translation is part of a group known as the ‘Caesarean’ text-type—a unique textual tradition believed to have circulated in the Near East during the first millennium.

Traditionally, scholars categorized New Testament manuscripts into three primary text-types: Alexandrian (found in early and reliable Greek manuscripts), Western (present in early translations and writings by church figures), and Byzantine (the basis for the King James Bible). The Caesarean text was suggested as an additional fourth type.

The existence of the Caesarean text-type has been debated; however, phylogenetic results now provide compelling evidence that these manuscripts are closely related. This Arabic translation proves to be an essential component in understanding this complex puzzle.

Beyond Biblical Manuscripts

“But this area of work has implications beyond the Bible.

See also: More Archaeology News

We can use the same techniques for any tradition shaped by scribes and copyists. At the moment, I am working with history researchers applying the same phylogenetics methods to the manuscripts of the Roman historian Livy.

The more precisely we can map how texts were copied and changed, the more clearly we can hear the voices of the ancient world – not as static monuments, but as living traditions shaped by human hands,” Dr. Turnbull, who is the author of the book Codex Sinaiticus Arabicus and Its Family, explains.

Written by Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com Staff Writer