The stuffy confines of the United States Patent Office could scarcely have presented a less romantic Valentine’s Day setting.

But on the morning of February 14, 1876, amid the thrum of clerks busying themselves within the heavily porticoed corridors of the federal monolith, a tale of passion, intrigue and bitter rivalry was steadily unfolding.

It began when the rather insistent lawyer of a prodigious inventor stepped up to demand that his client’s patent application for a newfangled apparatus called the telephone be registered without delay.

The lawyer’s urgency was well founded – owning the rights to a working phone system offered the prospect of fabulous wealth and, with others in the race with their own versions, time was of the essence.

Among them was an impoverished Italian immigrant, Antonio Meucci, and an American called Elisha Gray, who had contacted the office that day to lodge a caveat (a preliminary patent) for a similar device.

Unfortunately for Gray he was just too late – Library of Congress records reveal that his caveat was the 39th entry at the patent office in Washington DC that day while his rival, a certain Alexander Graham Bell, was fifth on the list.

To the winner, the spoils. And now, 150 years on from those tumultuous events, this Scottish genius is being rightly celebrated as the father of the telephone, one of the great inventions of the modern age.

Patent Number 174,465 was awarded the following month and became the most lucrative in history, giving his Bell Telephone Company (later American Telephone & Telegraph, or AT&T) a monopoly on this must-have piece of technology.

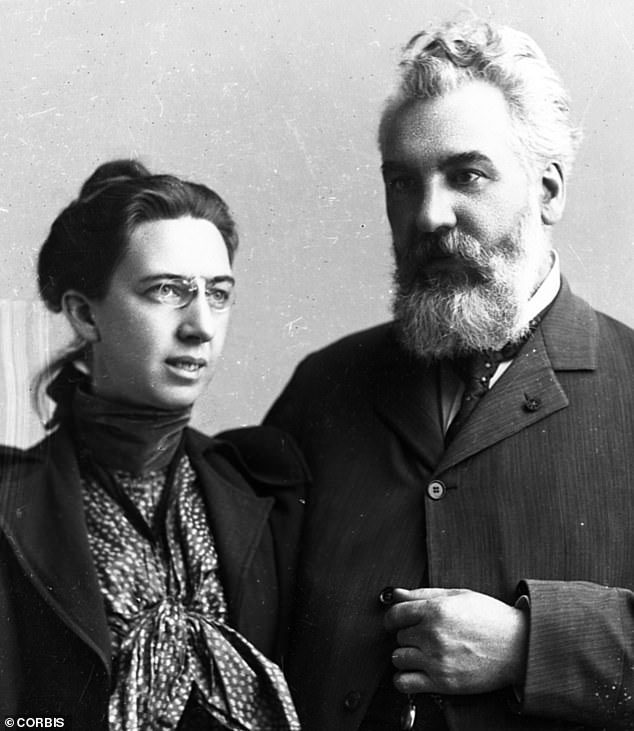

Alexander Graham Bell with his beloved wife Mabel

Things moved rapidly. On March 10 that year, Bell uttered the first clearly intelligible sentence over the phone, his crackly voice calling his business partner Thomas Watson from another room: ‘Mr Watson, come here, I want to see you.’ Hardly on a par with Neil Armstrong’s ‘One giant leap’ but no less significant.

Bell’s telephone was demonstrated at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia that summer, and the first two-way conversation over a significant distance took place in October.

Within a year of the demonstration, 100 pairs of telephones were sold. A month later the number had leapt to 778. The telephone had taken off.

Bell shrewdly applied for patents in the UK, mindful of its imperial reach, and his firm would eventually morph into a corporate giant.

His dream, that ‘a man in one part of the country may communicate by word of mouth with another in a distant place’, was realised. Even Bell may have been surprised at how far his dream has come since, with the telephone giving way to mobiles and then pocket-sized smartphones allowing a global community of billions to video-chat sweet nothings to their beloveds this February 14.

At the time, not everyone was impressed with Bell’s success. After losing out on their Valentine’s Day run-in, there was no love lost between Gray and Bell, who had to go to court many times to prove he came up with the idea first. He won all 587 lawsuits against him, including five in the Supreme Court.

Meucci also claimed to have invented a telephone system in 1855 but could not afford the $250 necessary to patent it. He too sued Bell during his lifetime but died before the case was resolved.

Few tears need be shed for Gray, though. Bell bought him out in the 1880s for the handsome sum of $100,000 and agreed that Gray’s firm would make all the Bell system’s equipment. Yet arguably the most intriguing aspect of Bell’s astonishing success was that it arose almost by chance out of his true passion in life: teaching deaf people how to speak. Unlike many of those who tried to claim his invention, Bell had no engineering background.

Bell’s invention was an instant success – paving the way for the long-distance romance

Rather, he had a fascination for sound.

Born plain Alexander Bell on March 3, 1847, in South Charlotte Street, in Edinburgh’s New Town, young Aleck was always tinkering as a child (he even got his father to change his birth details by adding the middle name Graham as an 11th birthday present).

He taught the family’s Skye terrier, Trouve, to growl continuously and, by manipulating its lips, got it to produce ‘Ow ah oo ga ma ma’: ‘How are you, grandmama?’ Aged 11, he invented a device made from rotating paddles and nail brushes for cleaning wheat, which friends used on their farm for years.

H IS father, Alexander Melville Bell, was a leading elocutionist (said to be the inspiration for George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion); his mother, Eliza, was a pianist who became profoundly deaf.

While Aleck’s fine ear also allowed him to master the piano, he plumped for a career in teaching the deaf like his father, who had invented Visible Speech, a method for teaching deaf people to speak that relied on sight, not hearing.

The Bells later moved to London but within three years tragedy had struck, and Bell Jnr lost both of his brothers to tuberculosis. His parents decided to emigrate to Canada, and persuaded their remaining son, then 23, to come with them, for the good of his own health.

While his parents settled in Ontario, Bell moved to Boston where he continued to teach the deaf, also giving private tuition to a beautiful deaf teenager, Mabel, the daughter of prominent lawyer Gardiner Greene Hubbard.

His interest in the science of sound led him to the fledgling field of communications technology, where the game was on to improve the electronic telegraph, the chief method of sending messages over distances, which was too slow and expensive to suit a rapidly modernising world.

By 1872, Bell was experimenting with multiple telegraphy – sending several messages down the same cable, using a variety of different pitches.

Within two years he was working on a much bigger idea: the possibility of transmitting the human voice.

It was Bell’s familiarity with sound and the crucial realisation that the complexities of the human voice can be transmitted not by a make-and-break current but by a continuous fluctuating one which gave him the edge.

By late 1874 Bell was writing to his parents about what he called ‘electric speech’.

The following July, he spoke, shouted and sang into an early transmitter while his colleague Watson listened downstairs. Muffled but unmistakable, the sounds came through.

It was Hubbard, by now backing Bell in his inventions, who realised there was no time to lose and filed for a US patent on his behalf.

Securing the patent provided lift-off in Bell’s private, as well as professional life, and a year later, he wed his Mabel. Their relationship was initially frowned on by both families: Bell’s father-in-law worried about Bell’s financial prospects while his own mother fretted that Mabel’s deafness was hereditary and would affect their children.

In fact, both fears proved unfounded as Mabel’s hearing problems were due to a bout of scarlet fever in childhood, while Bell was destined for great wealth.

Their loving marriage lasted 45 years and bore them two daughters, Elsie and Daisy (they also had two sons who died in infancy). As a wedding present, he gave Mabel a silver pendant in the shape of a telephone and all but ten of his 1,507 shares in his new telephone company.

Queen Victoria was keen to exploit the telephone’s extraordinary potential and on January 14, 1878, he gave her a personal demonstration at Osborne House, her Isle of Wight retreat. Impressed, she ordered a private line to be installed between Osborne House and Buckingham Palace. Further connections to Windsor Castle and Balmoral soon followed.

The telephone had grabbed the public’s imagination. By 1886, more than 150,000 people in the US owned one.

The very first phone book was a single sheet, issued in New Haven, Connecticut, in February 1878, while the first UK phone book followed two years later. The first entry was ‘John Adam & Co, 11 Pudding Lane, London’. Bell’s name was among the 248 subscribers listed.

His invention had made him wealthy and it helped to fund a lavish lifestyle in Nova Scotia. Despite becoming a US citizen in 1882, he and Mabel preferred to settle in Canada, which was said to remind Bell of Scotland.

In 1885, they bought a massive estate in Baddeck, Cape Breton Island, and built a mansion, Beinn Bhreagh (Gaelic for Beautiful Mountain), where he gave free rein to his inventive spirit.

A founding member of the National Geographic Society in 1888, Bell worked extensively in medical research and invented techniques for teaching speech to the deaf, while attempting new ideas involving kites, aeroplanes, sheep breeding, solar panels, composting toilets and a device to locate icebergs.

Bell died on August 2, 1922, aged 75, from diabetes-related complications not long after receiving a patent on the world’s fastest watercraft: the HD-4 hydrofoil. After his funeral, every phone in North America was silenced for a minute in his honour.

Ironically, Bell refused to have a telephone in his study, considering it a distraction from his scientific work.

Instead, on his desk was a photograph of his beloved Mabel. Written on the back was ‘the girl for whom the telephone was invented’.

As a Valentine’s Day gesture, that’s quite a call.