Even decades later, Patty Hearst says things will suddenly remind her of her infamous past as if it had ‘just happened.’

So, did a knock on her door last Wednesday plunge her back to the same evening in 1974 when unexpected callers at her apartment at 2603 Benvenue Avenue in Berkeley, California, would change her life forever?

On February 4, 1974, three strangers burst into her home with guns drawn, beating up the 19-year-old college sophomore’s fiancé, her former teacher Steven Weed, who was tied up along with a neighbor who had tried to help.

Witnesses saw a struggling and blindfolded Patty being frog-marched out to a waiting car. As the kidnappers fired wildly with their guns, she was bundled into the trunk and driven away.

Hearst was the heiress granddaughter of arguably America’s most famous media baron, Randolph G Hearst, and her captors were the warriors of the Marxist-inspired extremist group, the Symbionese Liberation Army. But within months, she’d be firing guns in US streets as she metamorphosed from abused hostage to rifle-toting, bank-robbing rebel.

And next month will mark the 50th anniversary of the end of an extraordinary trial in which she was jailed for seven years for the part she played in the SLA’s murderous spree.

It was a case which made Hearst the poster child for Stockholm Syndrome, a supposed psychological condition that explains why hostages sometimes unconsciously develop a bond with their captors or abusers. It had only been identified – and given its odd name – by a criminologist a few months earlier after four employees (three women and a man) of a Swedish bank developed a peculiar bond with the men attempting to rob it and became hostile towards police attempts to free them.

For many at the time, Hearst’s shocking behavior could only be adequately explained by Stockholm Syndrome.

Hearst was the heiress granddaughter of arguably America’s most famous media baron, Randolph G Hearst

Her captors were the warriors of the Marxist-inspired extremist group, the Symbionese Liberation Army. But within months, she’d be firing guns in US streets as she metamorphosed from abused hostage to rifle-toting, bank-robbing rebel

Since then, however, the condition has fallen out of favor with experts who say it is hardly supported by solid evidence and very likely doesn’t even exist.

Other explanations, they argue, could explain why victims behave this way, such as an instinctive survival mechanism which could prompt them to take any action – unlike Stockholm Syndrome, a very conscious action – that might protect them from harm.

And as Hearst would attest at her trial, she had been repeatedly threatened by her captors with death unless she could persuade them that she’d been converted to their unhinged political ideas and was ‘one of them’ now.

Stockholm Syndrome has also been condemned as implicitly misogynist. Most of those supposedly afflicted by it have – like Hearst – been women and critics have resented the way it seems to undermine their ordeal by suggesting their mental weakness is partly to blame.

Even without the speculation over Stockholm Syndrome, Hearst’s trial left a gobsmacked America sharply divided over whether – as she claimed in court –she’d been abused and brainwashed by the group or whether, excited by their outlaw life and radical ideas, she enthusiastically joined the party.

The precise reasons for Hearst’s alarming transformation from prisoner to predator remain shrouded in mystery. How much of it was involuntary and how much was her choice?

After all, can a young woman prepared to empty the entire magazine of an automatic rifle into the storefront (among myriad other violent crimes during more than a year on the run) really be a hostage? It’s a question that Hearst herself has never convincingly answered.

Born in San Francisco and educated at a succession of smart private schools, Hearst – one of five daughters of Hearst Corporation chairman Randolph Apperson Hearst – described herself as ‘sublimely self-confident’ as a child living in an affluent and sheltered home and enjoyed a privileged life that included horse-riding and debutante balls.

She wasn’t especially political although her college – the University of California, Berkeley – was a hotbed of left-wing protest.

She certainly wasn’t snatched at random. Her captors, whose full name of the United Federated Forces of the Symbionese Liberation Army reflected how some of these pitifully self-important groups had more words in their name than members, chose her because – correctly, as it turned out – they hoped her family’s fame would garner the attention that had hitherto eluded them. (The SLA had no trouble finding Hearst as a local newspaper had obligingly published her address when announcing her engagement.)

The group, which had been started by small-time crook Donald DeFreeze (who adopted the grandiose title of General Field Marshal Cinque) and ex-Berkeley scholar Patricia Soltysik, took its name from the word ‘symbiosis.’ Their incoherent ideology involved fighting for a political symbiosis of all left-wing groups including feminists, anti-racists and anti-capitalists.

Hearst became the poster child for Stockholm Syndrome, a psychological condition that explains why hostages sometimes unconsciously develop a bond with their captors or abusers

As Hearst (pictured during the robbery of the Hibernia Bank) would attest at her trial, she had been repeatedly threatened by her captors with death unless she could persuade them that she was ‘one of them’ now

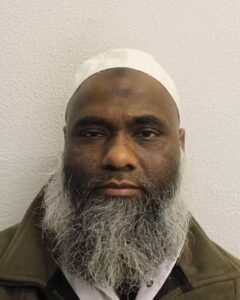

The group was started by small-time crook Donald DeFreeze (pictured), who adopted the grandiose title of General Field Marshal Cinque, and ex-Berkeley scholar Patricia Soltysik

Although they had no more than a dozen members, they proved they could be ruthless when, in 1973, they shot dead a pioneering black school superintendent and seriously wounded his deputy, using cyanide-tipped bullets.

Their victim had planned to introduce ID cards into Oakland schools – an act the SLA described as ‘fascist’ – and his death backfired, uniting black people and left-wingers against them.

Their hapless behavior continued when, after seizing Hearst, they demanded that her family donate free food to California’s poor. $2 million worth was distributed, but negotiations broke down after the hand-out demand increased to the point it would have cost the Hearsts an astonishing $400 million.

Patty Hearst would later say the group kept her locked up for 57 days in a closet barely big enough for her to lie down in, allowing her out to eat (still blindfolded) where she would be forced to listen to deranged political discussions and, later, join in. She was given a torch so she could memorize the SLA’s half-baked manifesto in her closet.

As well as the political indoctrination efforts, she said she was regularly told they were going to kill her and encouraged to join in the group’s policy of sexual freedom. The latter resulted, she said, in her being raped by the group’s leader, DeFreeze, and another man.

‘Blindfold, gagged, tied up,’ she said, adding that the close confinement was part of the group’s mission to brainwash her.

‘They debilitate you by locking you up,’ she told CNN’s Larry King in 1988. ‘You’re deprived of sight, light, sleep and food.’

According to Hearst, her captors gave her a bleak ultimatum – join them or die. She chose the former.

However, in a tape-recorded message released by the SLA two months after her capture, Hearst told a slightly different story. She claimed the group had offered to release her, but she decided to join them and fight ‘for the freedom of oppressed people.’ She insisted – at least on this occasion – she had suffered no abuse but had ‘changed – grown’ since being kidnapped.

The recorded message was accompanied by a photo of Hearst (who changed her name to Tania in tribute to a comrade of Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara) wearing a Che beret and brandishing an assault weapon in front of the SLA flag – a seven-headed serpent. It would become one of the most iconic images of 1970s America.

Shell-shocked Americans soon got a far more alarming glimpse of rebel Tania when, to show off their new recruit, the SLA robbed a San Francisco branch of the Hibernia Bank.

Bank surveillance cameras captured Hearst clutching an M-1 carbine as she screamed, ‘I’m Tania. Up, up, up against the wall, m***********s!’ Two bystanders were shot and wounded during the heist but not by her.

This photo of Hearst (who changed her name to Tania in tribute to a comrade of Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara) wearing a Che beret and brandishing an assault weapon in front of the SLA flag – a seven-headed serpent – would become one of the most iconic images of 1970s America

Six SLA members were killed in a blaze in Los Angeles when police surrounded the house they were holed up in

The fire started after gunfire erupted between the police officers and SLA members. Pictured is the rubble

The following month, she was the getaway driver when SLA members went to shoplift from a sporting goods store in Los Angeles. When they were confronted outside the store by staff, she pulled out an automatic rifle and fired wildly across the street. Miraculously, she failed to hit anyone but managed to extract her comrades and flee.

The next day, LA police surrounded a house where most of the group were holed up. Live TV followed the drama as a gun battle broke out that was so intense that the house caught fire. Six SLA members were killed but Hearst hadn’t been there.

She would later claim in her autobiography that the bloodbath convinced her that if she gave herself up, the police wouldn’t let her live.

After going on the run in Pennsylvania and New York, Hearst slipped back into California where she was involved in two more bank robberies, one of which resulted in a female customer being shot dead, as well as a plot to plant bombs under police cars.

She also helped hijack cars. A young man who was sitting in one of them found Hearst so friendly that he testified at her trial that she’d repeatedly asked if he was OK.

Nineteen months after she’d first been abducted, the FBI finally ran her to ground in San Francisco in September 1975.

The handcuffed heiress posed defiantly for the media, giving the clenched fist salute of the revolutionary and, when asked for her occupation as she was processed in a police station, gave ‘urban guerilla.’

The rebelliousness lasted just a few weeks in custody before Hearst repudiated her membership of the SLA and turned her mind to the pressing issue of getting off the hook.

She spoke at length to psychiatrists who helpfully came up with diagnoses such as brainwashing (backed up by her shrinking weight, memory and IQ) and ‘coercive persuasion’ suffered by prisoners of war.

Prosecutors weren’t impressed and produced their own psychiatrists, one of whom witheringly described Hearst as ‘a rebel in search of a cause’ during a court battle dubbed ‘the trial of the century,’ which started in January 1976.

Nineteen months after she’d first been abducted, she was arrested in San Francisco in September 1975

Hearst is pictured in the US Marshall’s car after a day in court in 1976

Hearst spoke at length to psychiatrists who helpfully came up with diagnoses such as brainwashing and ‘coercive persuasion’ suffered by prisoners of war

As she did her best to distance herself from the SLA, some of its surviving members hit back. In February, a mysterious bomb exploded at Hearst Castle, the palatial family seat in California.

Jailed SLA member Emily Harris gave an interview in which she claimed that Hearst had kept a trinket given to her by one of the men she said had raped her because she’d actually been in a romantic relationship with him. Meanwhile, a prosecutor assured the jury that the SLA’s female members had all been hardcore feminists and would never have allowed Hearst to be sexually assaulted.

And for all her repeated insistence that she’d been in fear of her life throughout her time with the ‘army’ and her lawyers producing photos which appeared to show other SLA members aiming their guns at her during bank robberies, prosecutors had little trouble flagging moments when she could easily have fled to safety.

On March 20, the jury rejected the abuse and brainwashing defenses, and Hearst was convicted of bank robbery and using a firearm while committing a felony. She was given the maximum sentence of 35 years, later reduced to seven.

In the event, she served even less than that. Hearst spent much of her prison time in solitary confinement for her own security – a dead rat she one day found on her bunk left little doubt what other SLA members thought of her. When she was released on bail in 1978 to appeal her sentence, her father hired a small army of bodyguards to protect her.

The appeal failed but she was soon released anyway in 1979 after President Jimmy Carter commuted her sentence to the 22 months served. President Bill Clinton granted her a pardon in 2001.

Two months after her release, she married Bernard Shaw, a police officer who’d been one of her bodyguards during her appeal. They moved to Connecticut and have two children, Gillian and Lydia, a fashion model. She later announced she preferred to be called Patricia.

She didn’t exactly shrink from the limelight. Eccentric director John Waters cast her in a string of feature films including the 1990 romantic comedy Cry Baby, black comedy Serial Mom (1994) and 2004 satire A Dirty Shame. She also had various TV roles including in the teen mystery series Veronica Mars. In 1996, the former gunslinger even wrote a murder mystery, set at Hearst Castle.

Hearst (pictured celebrating her commutation) was jailed for seven years, and her sentence was commuted in 1979 by President Carter

Hearst is pictured – alongside her fiancé at the time, Bernard Shaw – holding the executive grant of clemency in 1979

Hearts (pictured in 2019) went on to appear in movie and television roles as well as compete in dog shows

More recently, she started competing in dog shows – including the prestigious Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show – with her French bulldogs.

‘When people find out it’s me, it’s like it doesn’t make sense,’ she said in 2008 of this unlikely development in her life. ‘The Frenchie people know me because I’ve been around. But others, they seemed surprised.’

The wider jury of public opinion is still out over whether Hearst was a beaten-down victim or a zealous urban guerrilla.

Jeffrey Toobin, a lawyer and CNN legal analyst who wrote a 2016 biography of Hearst, is not convinced that she’s the former: ‘If you look at her actions … you see the actions of a revolutionary, not a victim.

‘There was some glamour to what she was doing, the swagger of wearing berets, of carrying machine guns — the romance of revolution was an undeniable part of the appeal of the SLA.’

Like the jurors at her trial, Toobin was not impressed by her endless failure to get away from her supposed captors.

‘She had multiple opportunities to escape over a year and a half,’ he told NPR. ‘She went to the hospital for poison oak, and she could’ve told the doctor, “Oh by the way, I’m Patty Hearst.” She was caught in an inaccessible place while hiking and the forest rangers helped her out, and she could’ve said, “Oh by the way, I’m Patty Hearst” … She didn’t escape because she didn’t want to escape.’

Politicians and celebrities spoke up for Hearst – even Hollywood star John Wayne complained at the unfairness of the court not accepting she’d been brain-washed. And two US presidents intervened on her behalf.

For seasoned lawyer Toobin, it amounted to ‘the purest example of privilege on display that frankly I have ever seen in the criminal justice system.’

For him and other skeptics, she remains the rich kid who played at being the gun-toting rebel, but who could rely on the power of the Hearst name when it all turned ugly.

She was never going to be an ideal champion for class war and revolution. And as the talk of Stockholm Syndrome has died to a whisper, it’s become increasingly hard to believe she was anything like the innocent she claimed to be.