At a beachfront convention center in Cancún, Mexico, last December, Seshadri Nadathur presented a confidential growth chart of the universe. Seated in the audience, hundreds of his fellow scientists silently processed that the cosmic chronicle as they had come to know it may need revising. “It’s the most exciting thing that’s happened in cosmology in 25 years,” says Nadathur, a cosmologist at the University of Portsmouth in England.

For almost three decades, astronomers have believed that the universe is expanding faster and faster and that the acceleration of this growth is constant over time—driven by a mysterious force they call “dark energy.” Last April a survey by the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) published hints that dark energy may not be as constant as they’d assumed, adding to a pile of concerns that are already threatening the standard model of cosmology. Today Nadathur and his DESI collaborators unveiled their follow-up results publicly at the American Physical Society’s Global Physics Summit and in multiple preprint papers, further validating the omen.

After nearly tripling the researchers’ collection of galaxy coordinates, the new DESI analysis provides the strongest evidence yet that the rate of cosmic expansion fluctuates—finally shedding some light on dark energy, which scientists think constitutes about 70 percent of everything in the universe.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Although the evidence still falls short of physicists’ benchmark for a “discovery,” experts say the new result leaves the standard model in dire straits. Making sense of an evolving dark energy would almost certainly involve amending the foundations of physics in order to unlock the true history and fate of our universe.

“It’s like hitting a vein of gold,” says Adam Riess, who shared the 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics for the discovery of dark energy and was not involved in the new work. Assuming the result holds up, “it says this investment that we’ve all been making that there was still more to learn is going to pay off.”

Cosmic Tug-of-War

Around a century ago scientists began to realize that the universe is expanding outward from what they now call the big bang, the explosion of energy that birthed space and time. In the late 1990s scientists set out to measure how the growth of the universe gradually slows as it spreads out—only to realize that it’s not slowing at all. Studying the light from burst stars called supernovae, Riess’s group and another independent team confirmed in 1998 that the farther objects are from us, the faster they’re receding. In other words, space is accelerating outward.

In the years since then, scientists have remained in the dark about what’s causing the universe’s prolonged growth spurt (hence the name “dark energy”). To construct their standard model of cosmology, theorists tagged onto their equations of gravity a “cosmological constant”—a value Albert Einstein first proposed in 1917 to explain why the universe doesn’t gravitationally collapse. Although physicists don’t understand the origin of this figure, their best guess has been that the vacuum of space itself is imbued with a constant energy that pushes outward relentlessly.

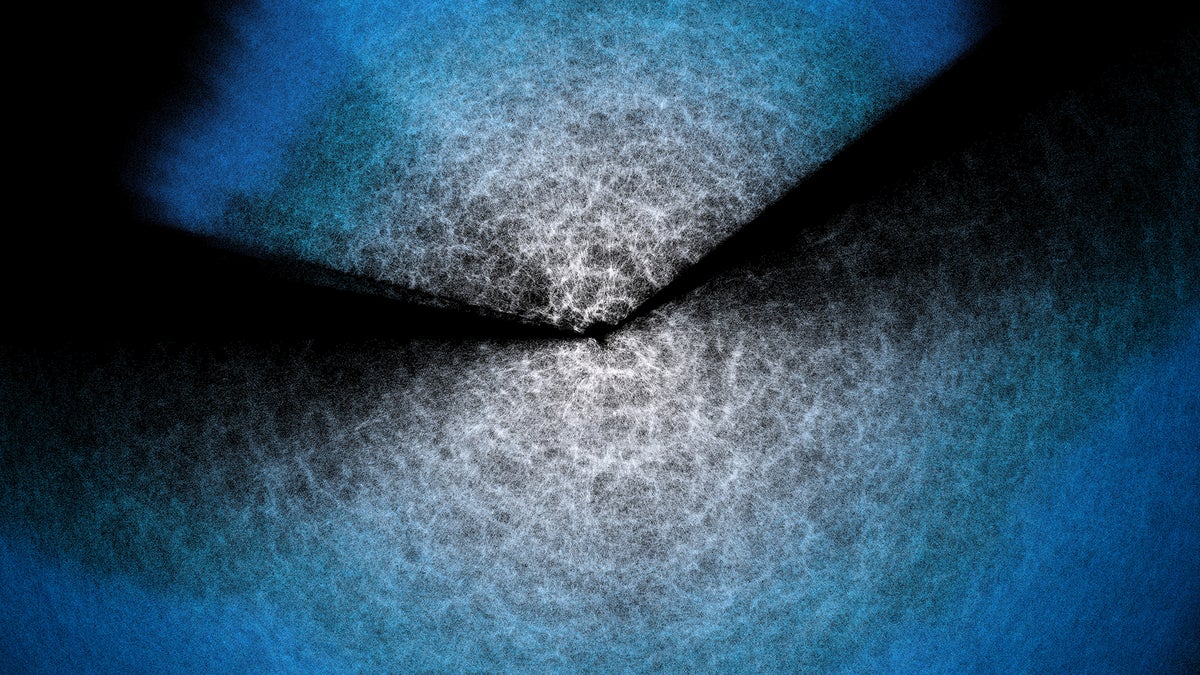

Today the canonical story of cosmic evolution describes this tug-of-war between the unwavering push of dark energy and the gravitational pull of matter (including the vast reservoirs of invisible “cold dark matter” that supposedly glue galaxies together). This standard model paints a “crazy successful” picture of how the universe evolved from one second to 14 billion years old, despite the fact that 95 percent of the model’s contents are utterly unfamiliar, says Kevork Abazajian, an astrophysicist at the University of California, Irvine. “But it’s also broken.” A series of conflicting measurements about the expansion rate and the clumpiness of the cosmos have thrown cosmology into a conundrum.

As a result, cosmologists have been measuring the rate at which nothingness expands with increasing precision. The acceleration had proven steadfast—until they started looking at sound.

Frozen Ripples in Space

Shortly after the big bang, the universe was a fireball of free-flying particles and light that sloshed around, creating pressure waves like those you’d get from tossing a rock into a pond. After around 380,000 years, everything had cooled enough for atoms to form, allowing light to flow freely without constantly bumping into other particles (this light is the cosmic microwave background radiation that we can still see today). Suddenly, the primordial pond froze over, preserving a patchwork of ripples, all about 490 million light-years across. These waves, known as baryonic acoustic oscillations, sowed the seeds for galaxies to come—offering astronomers today a handy standardized touchstone.

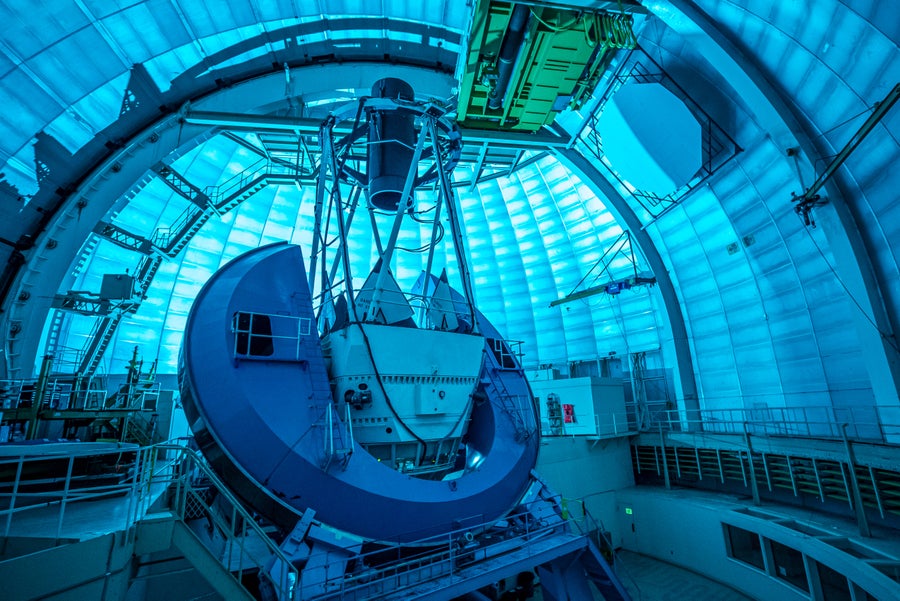

The Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) maps the universe by collecting spectra from millions of galaxies and quasars.

Marilyn Sargent/Berkeley Lab

Perched on the Quinlan Mountains in southern Arizona, DESI is designed to pick up those sound waves frozen in time. Its 5,000 dancing robotic arms trace out the patterns of galaxies, capturing more than 200,000 in a night. It then spits their light out into a spectrum, revealing the relative age of different clusters of galaxies. For objects more than nine billion light-years away, DESI detects matter by the way it soaks up light from supermassive black holes glowing in the background. At each slice of cosmic history, the team looks for traces of the ripples in the distribution of matter. Finally, by overlaying those measurements with observations of the cosmic microwave background and various supernovae surveys, the researchers can reconstruct a three-dimensional map of the universe’s expansion over the past 11 billion years.

Last April the 900-member DESI collaboration released the analysis of its first year of data, which showed some hints that the cosmic expansion rate didn’t line up perfectly with the standard model. But experts were hesitant to trust the signal from a brand-new experiment with limited observations. In this round, DESI has pinpointed nearly 15 million galaxies from more than 24,000 exposures—a few of which, observers suspect, were accidentally triggered by the telescope’s resident cat Mimzi stepping on the keyboard.

To avoid subconsciously biasing their interpretation, the researchers cleverly shuffled the real locations of galaxies such that their analysis wouldn’t reveal the true underlying cosmology to them while they were still working on it. After months of study, hundreds of DESI collaborators met in Cancún to “unblind” the results.

Days before the big reveal, a select few researchers quietly swapped in the true measurements and watched the plots slowly take shape. Uendert Andrade, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Michigan, spent the following days mustering his best poker face and dodging colleagues’ attempts to pry the answer out of him. “It’s really kind of magical—you’re one of the few people in the world that know this,” he says.

As Nadathur clicked through his presentation, the message became clear: The deviation wasn’t a fluke. The cracks in the standard model had only widened. “Something has to break somewhere,” says DESI collaborator Claire Lamman, a graduate student at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian.

On their own, the new DESI observations show a slight but statistically insignificant preference for an evolving dark energy. But when they are combined with other experiments’ data from supernovae surveys and the cosmic microwave background, the confidence that dark energy is indeed wavering approaches 99.997 percent—a compelling indication that’s just shy of the bar usually required to claim a physics discovery. Crucially, no matter which of those datasets are omitted, the results all point in the same direction. “You can remove one leg of the stool, and it still stands,” Riess says. “It passes the sniff test that I have for [taking] a result very seriously.”

Rewriting Physics

The analysis seems to suggest that dark energy transforms over time—appearing a tad weaker today than Einstein’s prediction and a tad stronger in the early universe. This progression has implications for the ultimate destiny of the universe: a dark energy that is too strong could eventually rip apart all atoms, and one that is too weak could lure everything to crunch inward.

Fate aside, the changeable nature of dark energy would pose deep problems for fundamental physics today. An acceleration greater than that described by the cosmological constant evokes what cosmologists call “phantom energy,” which has an ever increasing density over time—something forbidden by our current understanding of gravity.

Assuming the results stand, this incongruence could spark an era of “chaos cosmology,” says Abazajian, who recently posted a preprint paper that showed how even the previous DESI results prefer a fluctuating dark energy. Reconciling this, he suggests, would require either uncovering an entirely new fundamental force or realizing that our universe has more than four dimensions. “No matter what, we are discovering new physics here,” Abazajian says. “There’s nothing in the standard physics that allows for an evolving dark energy.”

Although the results don’t directly help to resolve the existing tensions in cosmology (relating to the universe’s stretching and smoothing), researchers are hopeful that the new insights could point them toward a sturdier model. Over the next few years, experiments with the Euclid satellite and the upcoming Vera C. Rubin Observatory should chime in with complementary pointers.

Researchers are already starting to mine the DESI data for clues. Riess is intrigued by why an evolving dark energy would hover around the value of the cosmological constant that Einstein predicted rather than any other arbitrary value. “It’s almost like an Easter egg—something is hidden in there,” he says.

For many senior members of DESI, the new results bring a feeling of relief. In graduate school, Alexie Leauthaud, now at the University of California, Santa Cruz, watched as fellow cosmologists debated whether their field was destined to die. They feared cosmology experiments would only measure the cosmological constant with greater precision to no avail. “It felt to many people that we were chasing these decimal points,” she says. “At least now we are headed somewhere.”

The significance rings differently for junior researchers. Lamman notes how ever since she’s been able to read, the cosmology textbooks haven’t changed. “This field has always been the same, and I’ve kind of taken that for granted,” she says. “I don’t think I ever fully internalized that we could actually find something new.”

After the unblinding, Lamman and a few dozen of her colleagues ran out to the beach to celebrate. Floating in the ocean, she gazed up at the blanket of stars and cried out at the sky, “We know your secret!”