February 14, 2026

4 min read

AI just got its toughest math test yet. The results are mixed

Experts gave AI 10 math problems to solve in a week. OpenAI, researchers and amateurs all gave it their best shot

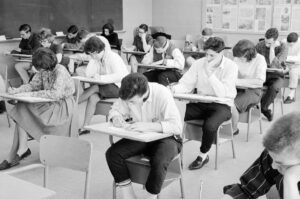

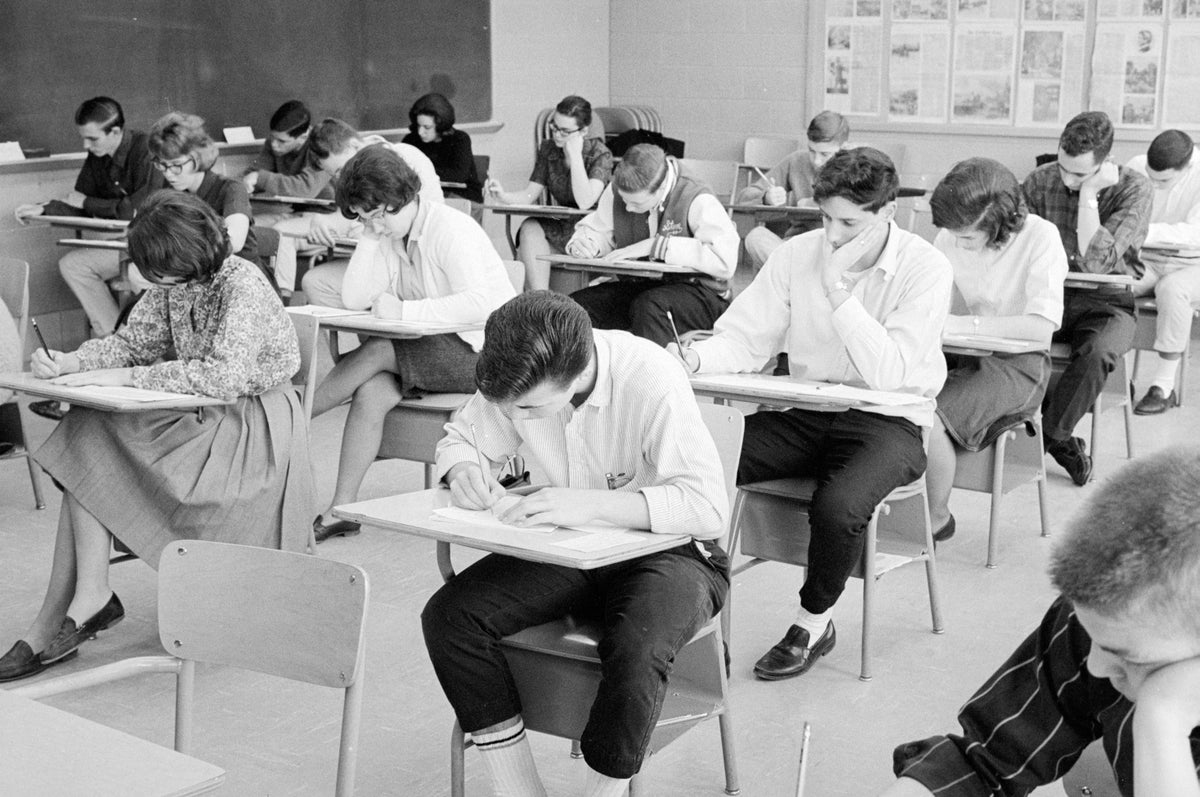

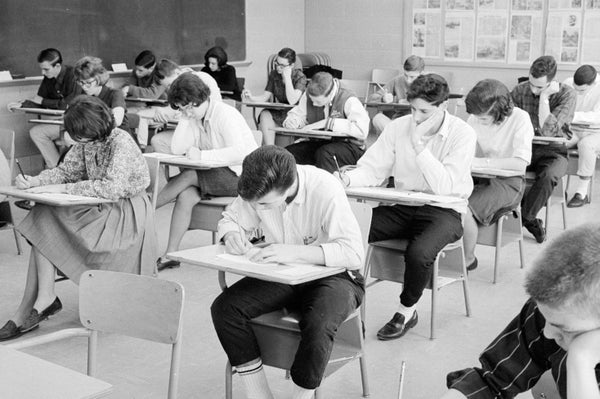

Interim Archives / Contributor via Getty Images

The verdict, it seems, is in: artificial intelligence is not about to replace mathematicians.

That is the immediate takeaway from the “First Proof” challenge—perhaps the most robust test yet of the ability of large language models (LLMs) to perform mathematical research. Set by 11 top mathematicians on February 5, the results of the test were released early in the morning on Valentine’s Day. It’s too soon to conclusively say how many of the 10 math problems that were included in the challenge were solved by AIs without human help. But one thing is clear: none of the LLMs came close to solving them all.

The mathematicians behind First Proof presented the AIs 10 “lemmas”—a math term for minor theorems that pave the way to a larger result. These problems are the working mathematician’s stock-in-trade, the kind of mini problem one might hand off to a talented graduate student. The mathematicians aimed for problems that would require some originality to solve, not just a mash-up of standard techniques, according to Mohammed Abouzaid, a math professor at Stanford University and a member of the First Proof team.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The challenge, while highlighting AI’s limitations, also spotlights a budding AI-enthusiast subculture within the mathematics community. Online discussion boards and social media accounts dedicated to math were swamped with purported proofs from top mathematicians and rogue undergraduates alike. And it underscored how seriously AI startups, including ChatGPT maker OpenAI, are taking the challenge of teaching an LLM to do math.

“We did not expect there would be this much activity,” Abouzaid says. “We did not expect that the AI companies would take it this seriously and put this much labor into it.”

The First Proof team revealed the solutions to the 10 challenges early on Saturday, and posted about their own experiences trying to get LLMs to solve the problems. They found that AIs could spit out confident proofs to every problem, but only two were correct—those for the ninth and 10th problems. And a proof that was nearly identical to the ninth problem turned out to already exist. The first problem was also “contaminated”—a sketch of a proof was archived from the website of its author, team member and 2014 Fields Medal winner Martin Hairer—but the LLMs still failed to fill in the gaps.

The style of proof that the LLMs came up with was particularly surprising, Abouzaid says. “The correct solutions that I’ve seen out of AI systems, they have the flavor of 19th-century mathematics,” he says. “But we’re trying to build the mathematics of the 21st century.”

Outside submissions didn’t appear to fare much better. Some submissions appeared to employ varying degrees of human input, with several seemingly the result of week-long dialogues checked by mathematicians. Importantly, the First Proof rules disallow human mathematical input or prodding.

“Once there’s humans involved, how do we judge how much is human and how much is AI?” says Lauren Williams, Dwight Parker Robinson Professor of Mathematics at Harvard University and one of the mathematicians who set up First Proof.

OpenAI posted its work on Saturday, the result of a week-long sprint using its newest in-house AI models working with “expert feedback” from human mathematicians. The company’s chief scientist Jakub Pachocki said in a social media post that they believe six of their ten solutions to “have a high chance of being correct.” Mathematicians have pointed to potential holes in at least one of those six already.

Aside from how much human assistance the AIs had, the vast bulk of the submissions appear to be a lot of very convincing nonsense. Before the challenge had even ended, a number of purported solutions that initially appeared credible were already being questioned by experts.

The submissions will take days for experts to properly vet. And judging whether a proof is truly “original” is even tougher than judging if it is correct. “Nothing in math is totally without precedent,” says Daniel Litt, a mathematician at the University of Toronto, who was not part of the First Proof team.

“We are thinking of this as an experiment. Our goal was to get feedback,” Abouzaid says. The team writes that they’re planning a second round with tighter controls, and that more more details will be released on March 14.

For some mathematicians who’ve been tracking AI’s progress, the lukewarm results match their expectations. “I expected maybe two to three unambiguously correct solutions from publicly available models,” Litt says. “Ten would have been very surprising to me.”

Still, even getting a few valid solutions to research-level problems from an AI would likely have been impossible just months ago. “I already have heard from colleagues that they are in shock,” says Scott Armstrong, a mathematician at Sorbonne University in France. “These tools are coming to change mathematics, and it’s happening now.”

But for others who closely track AI’s achievements, this wasn’t a great showing.

“The models seem to have struggled,” says Kevin Barreto, an undergraduate student at the University of Cambridge, who was not part of the First Proof team. He recently used AI to solve one of the Erdős problems, a number of challenges posed by Hungarian mathematician Paul Erdős. “To be honest, yeah, I’m somewhat disappointed.”

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.