Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com – A groundbreaking DNA study has unveiled the secrets behind the remarkable success of the Phoenician-Punic Civilization, along with an unexpected discovery that could reshape our understanding of ancient history.

Emerging from the Bronze Age city-states of the Levant, Phoenician culture introduced significant innovations like the first alphabet, which laid the foundation for many modern writing systems. By the early first millennium BCE, these cities had established an extensive maritime network that reached as far as Iberia, effectively spreading their culture, religion, and language across the central and western Mediterranean regions.

By the 6th century BCE, Carthage, a thriving Phoenician colony in present-day Tunisia, had ascended to regional dominance. The Romans referred to these culturally rich communities associated with or governed by Carthage as “Punic.” The Carthaginian empire is etched in history for its notable conflicts with Rome during three major “Punic Wars,” including General Hannibal’s audacious campaign over the Alps.

Now, under a collaborative effort led by Johannes Krause from Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and Michael McCormick of Harvard University at the Max Planck-Harvard Research Center for Archaeoscience of Ancient Mediterranean civilizations, researchers have embarked on a fascinating journey into genetic history.

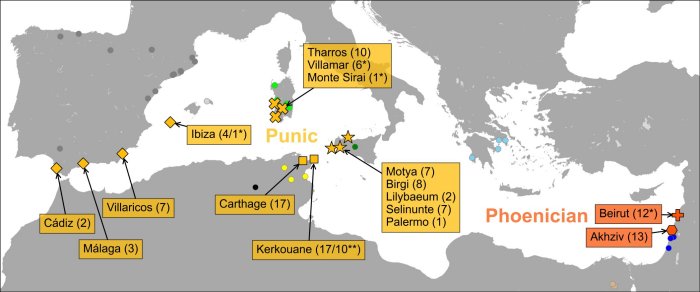

Map of sites included in the aDNA study (approximately 600 BCE). The numbers indicate the number of human genomes produced from these sites. Credit: Harald Ringbauer

This new study utilizes ancient DNA to explore Punic ancestry and seeks genetic connections between them and their Levantine Phoenician counterparts who shared cultural and linguistic ties. By sequencing genomes from human remains found at 14 archaeological sites across regions such as North Africa, Iberia, Sicily, Sardinia, Ibiza, and beyond, the research offers compelling insights that invite us all to reconsider what we know about these influential ancient societies.

The researchers revealed an unexpected result.

“We find surprisingly little direct genetic contribution from Levantine Phoenicians to western and central Mediterranean Punic populations,” says lead author Harald Ringbauer, who was a post-doctoral scientist at Harvard University when he began this research, and is now a group leader at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, in a press release.

Punic Necropolis of Puig des Molins on the island of Ibiza. The new ancient DNA study sequenced human remains from this and other important Phoenician-Punic archaeological sites. Credit: Raymar, MAEF

“This provides a new perspective on how Phoenician culture spread—not through large-scale mass migration, but through a dynamic process of cultural transmission and assimilation.”

The study highlights that Punic sites were home to people with vastly different ancestry profiles. “We observe a genetic profile in the Punic world that was extraordinarily heterogeneous,” says David Reich, a professor of Genetics and Human Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University who co-led the work.

“At each site, people were highly variable in their ancestry, with the largest genetic source being people similar to contemporary people of Sicily and the Aegean, and many people with significant North African associated ancestry as well.”

The findings highlight the cosmopolitan nature of the Punic world, where individuals of North African ancestry coexisted and interacted with a predominantly Sicilian and Aegean population across all examined Punic sites, including Carthage. Genetic networks throughout the Mediterranean suggest that shared demographic processes, including trade, intermarriage, and population mixing, played a crucial role in forming these communities.

Notably, researchers discovered a pair of close relatives (approximately second cousins) who were connected to the Mediterranean region, with one buried at a North African Punic site and the other in Sicily.

See also: More Archaeology News

These findings strongly support the notion that ancient Mediterranean societies were intricately linked, with individuals frequently traveling and mingling across vast geographic areas.

This research underscores the remarkable capability of ancient DNA to illuminate the ancestry and movement of historical populations, especially those for which direct historical records are limited

The study was published in Nature

Written by Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com Staff Writer