Conny Waters – AncientPages.com – The ancient pyramids captivate us with their mysteries, and each archaeological discovery brings us closer to understanding their secrets. The recent discovery made in ancient burial chambers of the pyramids in Tombos is particularly intriguing, as it could reshape our understanding of ancient Egyptian civilization.

Since the early examinations of Egyptian pyramids, it has been widely accepted that these grand structures primarily functioned as burial sites for ancient society’s leaders. However, recent research is prompting a reevaluation of this belief.

Sarah Schrader and her team from Leiden University in the Netherlands have conducted research at the site of Tombos, located at the Third Cataract of the Nile. This area was inhabited from the 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom through to the Late period, approximately 1400–650 BCE. Following Egypt’s conquest of Nubia, Tombos was established by Egyptians within Nubian territory as a means to exert colonial control. This strategic move aimed to foster coexistence with local populations and marked a departure from previous colonization efforts in Nubia. Archaeological and bioarchaeological findings indicate that Egyptians and Nubians cohabited this colonial space, leading to intertwined social and biological lives.

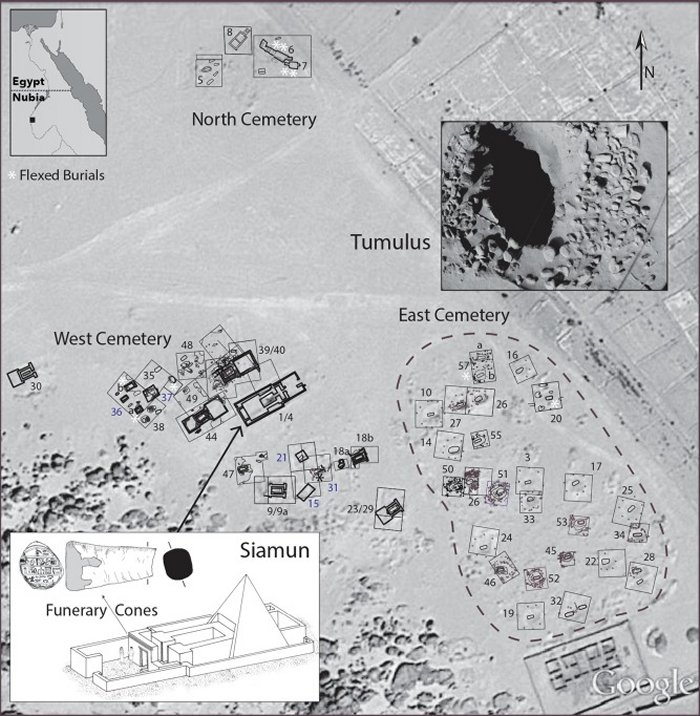

Plan of Tombos Cemetery (Highlighting the three main cemetery areas: North, West, and East; Illustrating examples of tumulus and pyramid burial structures). Credit: S. Schrader et al.

Osteological analysis reveals that this population experienced relatively good health, with minimal signs of physiological stress evident in their skeletal remains. Furthermore, instances of interpersonal violence were notably low compared to earlier Nubian societies, suggesting a predominantly peaceful environment during this period.

Pyramid tombs in Tombos were initially thought to be reserved for the elite. Yet, new analyses of approximately 3,500-year-old human remains found in burial chambers reveal that individuals from hardworking and likely lower social classes were also buried in these pyramids. This discovery suggests a more complex social structure surrounding pyramid burials than previously understood.

Researchers uncovered their findings by analyzing minute marks on thousands of-year-old human bones. These marks reveal the attachment points of muscles, ligaments, and tendons to the bones. By studying these indicators, scientists can judge the level of physical activity that individuals engaged in during their lifetimes.

The discovery of skeletal remains from inactive individuals aligns with expectations, as these likely belonged to wealthy Egyptians who had servants and slaves attending to them. Researchers anticipated finding such remains in the tombs. However, the presence of physically active individuals was unexpected. These remains are believed to belong to slaves, servants, or lower-ranking Egyptians. As noted in the researchers’ new study, this finding has the potential to alter our understanding of Egyptian burial rituals and the role of pyramids.

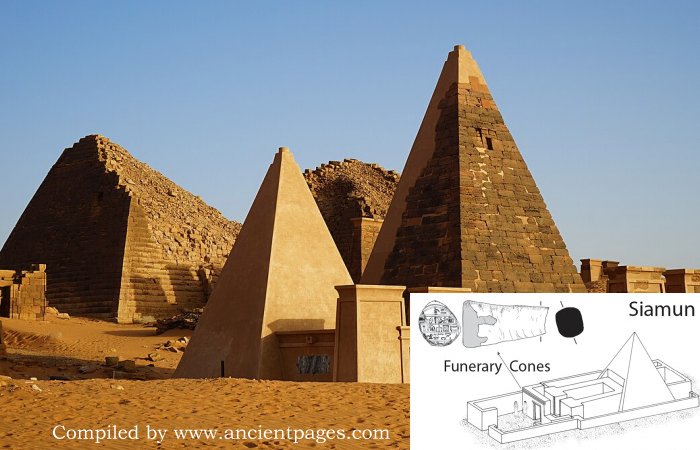

Credit: Clemens Schmillen – CC BY-SA 4.0

According to the study, “the most elaborate tomb at Tombos was dedicated to the Scribe Accountant of the Gold of Kush Siamun, a title that suggests an important role in assembling the Kushite contribution to the annual Presentation ceremony given the site’s proximity to the former Kushite capital at Kerma.

The combination of burial practice and entheseal changes suggests that he brought with him an entourage who were engaged in various activities that supported his mission, likely a combination of diplomacy, surveillance, and the periodic assembly and transshipment of goods to the north. Skilled staff would include scribes like Tahut, priests like Hapy, and various supervisors to manage the colonial workforce, weigh gold, etc., perhaps reflected in the individuals with light entheseal wear.

Laborers would be required for constructing and maintaining the mud brick buildings of the settlement and cemetery, as well as the large fortified enclosure that surrounded it. If Tombos served as a transshipment point, then workers would be required to move goods from place to place and load caravans and/or ships for the trip to Egypt.”

Researchers point out that an individual’s social status can often be inferred by examining mortuary practices, such as the presence of grave goods and containers and the burial’s location within a tomb. However, factors like other treatments and disturbances can complicate these assessments. Additionally, the use of collective tombs and their reuse was a significant practice in New Kingdom Nubia.

See also: More Archaeology News

“We can no longer assume that individuals buried in grandiose pyramids tombs are the elite. Indeed, the hardest working members of the communities are associated with the most visible monuments. Colonial administrators could have encouraged this practice in order to inscribe a hierarchical social order on the sacred landscape of the cemetery.

In contrast, the northern cemetery by and large reflects a group of people who led a relatively leisurely lifestyle consistent with family groups,” the researchers conclude in their study.

The study was published in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology

Written by Conny Waters – AncientPages.com Staff Writer