Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com – A significant scientific breakthrough has been achieved by a team of researchers who have successfully extracted and sequenced the oldest known Egyptian DNA. This DNA comes from an individual who lived approximately 4,500 to 4,800 years ago, during the era of the first pyramids.

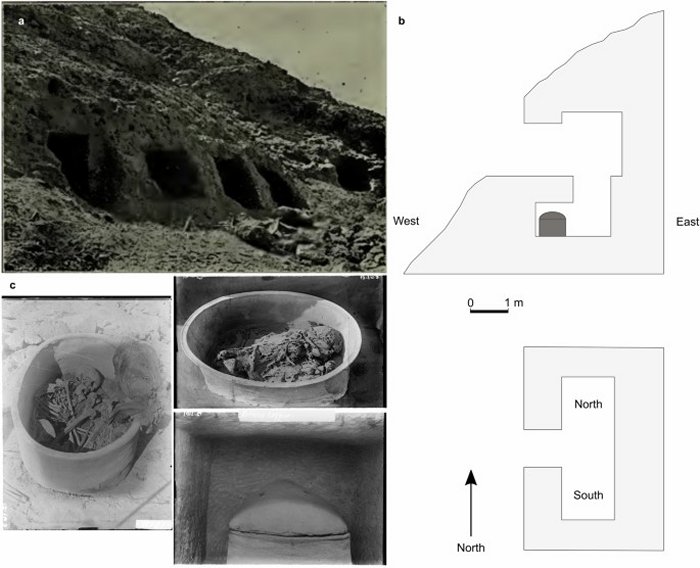

The individual was buried in a ceramic pot within a hillside tomb before artificial mummification became common practice, which likely contributed to the preservation of his DNA.

The burial site was originally donated by the Egyptian Antiquities Service to an excavation committee led by John Garstang during British rule. It was initially housed at the Liverpool Institute of Archaeology. It later became part of the World Museum Liverpool.

This achievement comes forty years after Nobel laureate Svante Pääbo’s initial attempts to extract ancient DNA from Egyptian remains, made possible now through advancements in technology that have enabled sequencing of this first whole genome from ancient Egypt.

During this historical period, archaeological evidence indicated trade and cultural exchanges with regions like the Fertile Crescent—comprising modern-day Iraq, Iran, and Jordan—though genetic evidence had been scarce due to warm climates affecting DNA preservation. In their study, researchers from the Francis Crick Institute and Liverpool John Moores University extracted DNA from a tooth found in Nuwayrat village, located 265 km south of Cairo. Analysis revealed that most ancestry traced back to North African populations, with about 20% linked to ancient individuals from Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq).

This discovery provides genetic proof of population movement into Egypt and integration with local communities—a phenomenon previously inferred only through artifacts. However, scientists emphasize that more genome sequences are necessary for a comprehensive understanding of ancestral diversity in ancient Egypt.

a, Final facial depiction of the Nuwayrat individual. b, Virtual fit of the skull and facial reconstruction. c, The Nuwayrat individual’s partially complete skeleton. Credit: Nature

Additionally, chemical signals analyzed in his teeth suggest he grew up locally within Egypt. Skeletal analysis provided insights into his sex, age at death, height potentia,l as well as lifestyle indicators suggesting he might have worked as a potter or engaged in similar trades requiring prolonged sitting positions with extended limbs due to muscle markings observed on his bones.

“Piecing together all the clues from this individual’s DNA, bones and teeth have allowed us to build a comprehensive picture. We hope that future DNA samples from ancient Egypt can expand on when precisely this movement from West Asia started,” Adeline Morez Jacobs, Visiting Research Fellow and former Ph.D. student at Liverpool John Moores University, former postdoctoral researcher at the Crick and first author, said.

“This individual has been on an extraordinary journey. He lived and died during a critical period of change in ancient Egypt, and his skeleton was excavated in 1902 and donated to World Museum Liverpool, where it then survived bombings during the Blitz that destroyed most of the human remains in their collection.

We’ve now been able to tell part of the individual’s story, finding that some of his ancestry came from the Fertile Crescent, highlighting mixture between groups at this time,” Linus Girdland Flink, Lecturer in Ancient Biomolecules at the University of Aberdeen, Visiting Researcher at LJMU and co-senior author, said.

“Forty years have passed since the early pioneering attempts to retrieve DNA from mummies without successful sequencing of an ancient Egyptian genome.

Ancient Egypt is a place of extraordinary written history and archaeology, but challenging DNA preservation has meant that no genomic record of ancestry in early Egypt has been available for comparison.

a, Rock-cut tombs at Nuwayrat enclosing the pottery vessel containing the pottery coffin burial. b, An impression of the rock-cut tomb based on the archaeologist John Garstang’s description, with the pottery coffin burial in the south burial chamber. c, Pottery coffin and archaeological remains of the Nuwayrat individual, as discovered in 1902. Photos in a and c reproduced courtesy of the Garstang Museum of Archaeology, University of Liverpool. Credit: Nature

Building on this past research, new and powerful genetic techniques have allowed us to cross these technical boundaries and rule out contaminating DNA, providing the first genetic evidence for potential movements of people in Egypt at this time,” Pontus Skoglund, Group Leader of the Ancient Genomics Laboratory at the Crick and co-senior author, said.

Joel Irish, Professor of Anthropology and Archaeology at Liverpool John Moores University and second author, said, “The markings on the skeleton are clues to the individual’s life and lifestyle—his seat bones are expanded in size, his arms showed evidence of extensive movement back and forth, and there’s substantial arthritis in just the right foot.

See also: More Archaeology News

“Though circumstantial, these clues point towards pottery, including the use of a pottery wheel, which arrived in Egypt around the same time. That said, his higher-class burial is not expected for a potter, who would not normally receive such treatment. Perhaps he was exceptionally skilled or successful to advance his social status.”

In future work, the research team hopes to build a bigger picture of migration and ancestry in collaboration with Egyptian researchers.

The study was published in the journal Nature.

Written by Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com Staff Writer