February 19, 2026

3 min read

‘Mind-blowing’ baby chick study challenges a theory of how humans evolved language

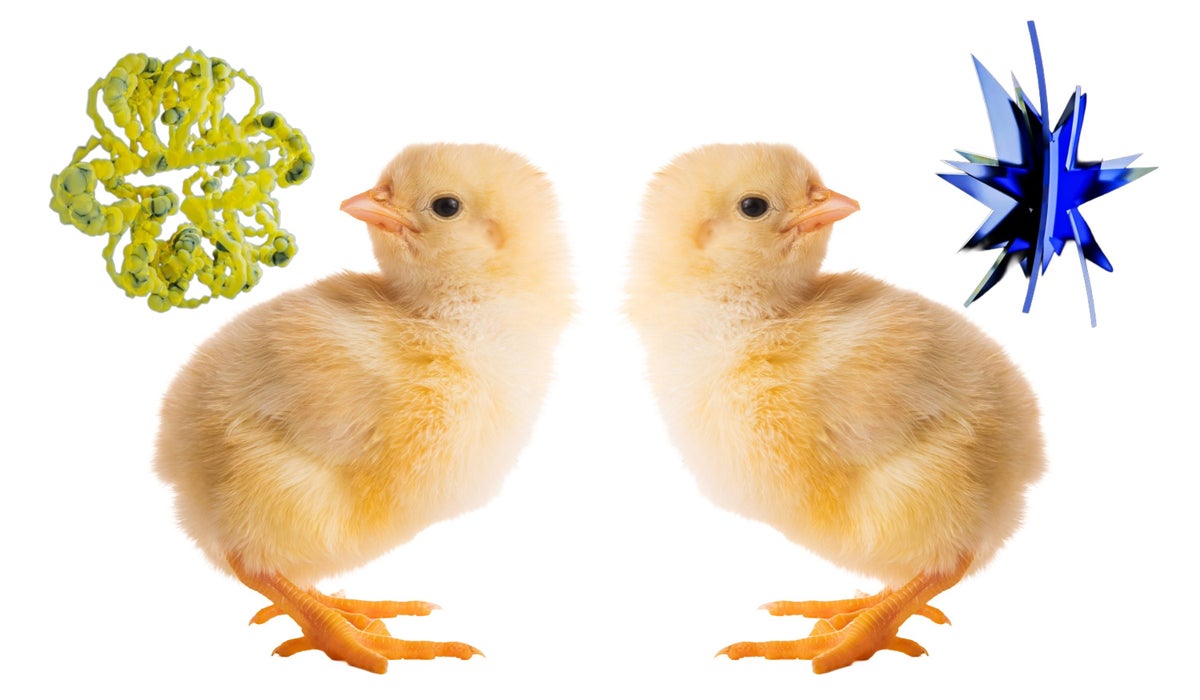

Newborn chicks connect sounds with shapes just like humans, suggesting deep evolutionary roots of the “bouba-kiki” effect

HUIZENG HU/Getty Images (photography); Jeffery DelViscio (illustrations)

Why does “bouba” sound round and “kiki” sound spiky? This intuition that ties certain sounds to shapes is oddly reliable all over the world, and for at least a century, scientists have considered it a clue to the origin of language, theorizing that maybe our ancestors built their first words upon these instinctive associations between sound and meaning. But now a new study adds an unexpected twist: baby chickens make these same sound-shape connections, suggesting that the link to human language may not be so unique.

The results, published today in Science, challenge a long-standing theory about the so-called bouba-kiki effect: that it might explain how humans first tethered meaning to sound to create language. Perhaps, the thinking goes, people just naturally agree on certain associations between shapes and sounds because of some innate feature of our brain or our world. But if the barnyard hen also agrees with such associations, you might wonder if we’ve been pecking at the wrong linguistic seed.

Maria Loconsole, a comparative psychologist at the University of Padua in Italy, and her colleagues decided to investigate the bouba-kiki effect in baby chicks because the birds could be tested almost immediately after hatching, before their brain would be influenced by exposure to the world. The researchers placed chicks in front of two panels: one featured a flowerlike shape with gently rounded curves; the other had a spiky blotch reminiscent of a cartoon explosion. They then played recordings of humans saying either “bouba” or “kiki” and observed the birds’ behavior. When the chicks heard “bouba,” 80 percent of them approached the round shape first and spent an average of more than three minutes exploring it compared with an average of just under one minute spent exploring the spiky shape. The exploration preferences were flipped when the chicks heard “kiki.”

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Because the tests took place within the chicks’ carefully supervised first hours of life outside their eggshell, this association between particular sounds and shapes couldn’t have been learned from experience. Instead it may be evidence of an innate perceptual bias that goes back way farther in our evolutionary history than previously believed.

“We parted with birds on the evolutionary line 300 million years ago,” says Aleksandra Ćwiek, a linguist at Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, Poland, who was not involved in the study. “It’s just mind-blowing.”

In a 2022 paper Ćwiek and her colleagues demonstrated that the bouba-kiki effect held across diverse cultures and writing systems worldwide. Other experiments have found that human infants perform similarly on these tests, even before they’ve learned to speak. And in 2019 and 2022 researchers tested the effect in great apes and found that they failed the bouba-kiki test, which further strengthened the idea that the effect was exclusive to humans and our linguistic capabilities.

Loconsole argues that the apes’ prior communicative training may have skewed their performance. Jared Taglialatela, director of the Ape Initiative and co-author of one of the ape studies, agrees. The study’s subject, Kanzi the bonobo, who recently passed away, was often given similar language-related tests. It’s possible that when Kanzi encountered these new nonsense words, he tried to guess their “meaning” rather than follow his gut association.

In light of the new chick findings, Ćwiek has also taken a broader view. “It actually makes the question of bouba-kiki being a solution to language evolution less interesting because it is prelanguage,” she says. “I think it shows us something deeper about cognition, about the capacity for connecting senses.”

As for what on Earth makes “bouba” round and “kiki” spiky, we may be able to rule out one long-standing theory: that these associations are inspired by the shape your mouth makes when you say each word. While the “b” sound does require rounding your lips, and the “k” sound calls for an explosive tap to the roof of your mouth, chickens obviously can’t say them at all. Instead the bouba-kiki effect may stem from the physical properties of objects themselves, as some researchers have suggested. When round objects hit the ground or roll, they typically produce more continuous, low-frequency sounds than spiky ones. A built-in grasp of those dynamics, linking sight and sound, could help newborn animals quickly make sense of their environment, possibly to locate food or avoid predators.

The bouba-kiki effect may have played a role in the emergence of language, along with many other cognitive faculties. But for chickens (and presumably other animals), these same predispositions seem to serve a more evolutionarily ancient purpose. “Even if language [is] unique to humans,” Loconsole says, “that doesn’t mean that it comes from an ability that is unique to humans.”

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.