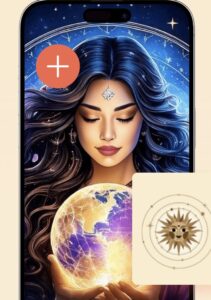

Artist’s impression of an encounter between an ancient caiman and a terror bird

Julian Bayona Becerra

About 13 million years ago in a vast South American wetland, colossal predators clashed. The fossilised bone from an enormous flightless bird found in Colombia shows tooth marks made by a giant caiman.

Andrés Link at the University of the Andes in Colombia and his colleagues were studying crocodile fossils in a museum collection when they realised one of the bones didn’t fit. It turned out to belong to a phorusrhacid bird – a group also known as the “terror birds”. These top predators had hatchet-shaped beaks and powerful legs with sharp claws on their toes. The fossilised bone came from the lower leg of a 2.5-metre-tall species, possibly one of the largest types of terror bird yet discovered.

But this predator may have met a grisly end. The bone, originally discovered in Colombia’s Tatacoa desert region by local palaeontologist César Perdomo, was scarred with four deep divots: teeth marks.

Link and his team wanted to know what beast dared wrap its jaws around such an intimidating predator. So they scanned the surface of the fossil to generate a digital model of the tooth marks and compared them with the teeth of ancient predators from the region. The culprit likely wasn’t a mammal.

“There’s no evidence of gnawing and the marks are rounded and in [a] line, more similar to those inflicted by crocodiles and caimans,” says Link.

The terror bird lived at a time when northern South America was dominated by the Pebas system, a massive network of wetlands interspersed with tropical forests and grasslands. The flooded ecosystem hosted a great diversity of crocodilians, and the team found a match for the teeth marks in one of them: a giant caiman called Purussaurus neivensis. Link estimates the reptile would have been about 4.5 metres long.

“Terror birds were undoubtedly at the top of the food chain,” says Link. “But this evidence shows us that they could also fall as prey of large caimans when approaching large water bodies. Maybe they went there to look for prey or [were] moving across this complex ecosystem.”

The team notes they can’t rule out the possibility the bird was already dead when the caiman found it, and the tooth marks are evidence of scavenging. There are no signs of bone healing around the tooth marks. So either way, the bird didn’t survive the encounter.

“These kinds of [tooth] traces are more common than people think,” says Carolina Acosta Hospitaleche at the National University of La Plata in Argentina.

In a study published last year, she and a colleague described tooth marks on a much smaller and older terror bird fossil – roughly 43 million years old – from Argentina. The markings suggest an ancient carnivorous marsupial fed on that bird. Since those traces were also on the lower leg, Hospitaleche wonders if that part of the terror bird body was a vulnerable place for predators to chomp and grip their prey.

“[Bite marks] provide us with these amazing little snapshots into life in the past,” says Stephanie Drumheller at the University of Tennessee.

When studying ancient environments, there is a tendency to attempt to precisely categorise extinct organisms within particular ecological roles, she says. However, food webs can be complex.

“This is an animal that was living in the water and doing things in the water, this is an animal that was living up on land and doing things upon land, and never the two shall meet,” says Drumheller. “But of course, nature is always messier than our nice, little, neat boxes.”

Topics: