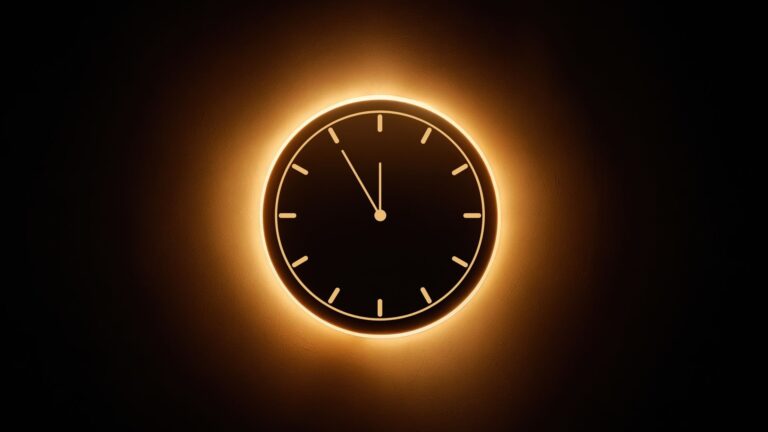

A Cornell physicist has calculated that the universe may be nearing the halfway point of a total lifespan of about 33 billion years. Using newly released data from major dark energy observatories, he concludes that the cosmos will continue expanding for roughly another 11 billion years before reaching its largest size. After that, it would begin to shrink, eventually collapsing back into a single point, much like a stretched rubber band snapping back.

Henry Tye, the Horace White Professor of Physics Emeritus in the College of Arts and Sciences, arrived at this conclusion by updating a long standing model built around the “cosmological constant.” This concept was first introduced more than a century ago by Albert Einstein and has been central to modern predictions about how the universe will evolve.

“For the last 20 years, people believed that the cosmological constant is positive, and the universe will expand forever,” Tye said. “The new data seem to indicate that the cosmological constant is negative, and that the universe will end in a big crunch.”

Tye is the corresponding author of “The Lifespan of our Universe,” published in the Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics.

Big Crunch Versus Endless Expansion

The universe is currently 13.8 billion years old and still expanding. Standard cosmology outlines two straightforward possibilities. If the cosmological constant is positive, expansion continues indefinitely. If it is negative, the universe would eventually stop growing, reach a maximum size, and then reverse direction, contracting until everything collapses to zero.

Tye’s updated model supports the second outcome.

“This big crunch defines the end of the universe,” Tye wrote. Based on his calculations, that collapse would occur in about 20 billion years.

Dark Energy Data From DES and DESI

Key evidence comes from new findings released this year by the Dark Energy Survey (DES) in Chile and the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) in Arizona. Tye noted that results from these two observatories, located in opposite hemispheres, closely agree with each other.

Both projects aim to better understand dark energy, which makes up about 68% of the mass and energy in the universe. Their goal is to test whether dark energy is simply a constant property of space itself. Instead, the data suggest the situation may be more complex. The universe does not appear to be governed solely by a pure cosmological constant. Something additional may be influencing how dark energy behaves.

To account for this, Tye and his collaborators proposed a hypothetical particle with extremely low mass. Early in cosmic history, this particle would have acted like a cosmological constant, but over time its effects would have changed. This adjustment fits the latest observations and pushes the underlying cosmological constant into negative territory.

“People have said before that if the cosmological constant is negative, then the universe will collapse eventually. That’s not new,” Tye said. “However, here the model tells you when the universe collapses and how it collapses.”

Ongoing Observations and Future Tests

More data are on the way. Hundreds of researchers are studying millions of galaxies and measuring the distances between them to refine estimates of dark energy. DESI will continue collecting observations for another year. Additional projects are already contributing or preparing to begin, including the Zwicky Transient Facility in San Diego; the European Euclid space telescope; NASA’s recently launched SPHEREx mission; and the Vera C. Rubin Observatory (named after Vera Rubin, M.S. ’51).

Understanding the Beginning and the End

Tye says it is encouraging that scientists can attempt to calculate the total lifespan of the universe in measurable terms. Identifying both the starting point and the eventual conclusion helps cosmologists better understand the full story of cosmic history.

“For any life, you want to know how life begins and how life ends — the end points,” he said. “For our universe, it’s also interesting to know, does it have a beginning? In the 1960s, we learned that it has a beginning. Then the next question is, ‘Does it have an end?’ For many years, many people thought it would just go on forever. It’s good to know that, if the data holds up, the universe will have an end.”

Tye’s co-authors are his former Hong Kong University of Science and Technology doctoral students Hoang Nhan Luu and Yu-Cheng Qiu.