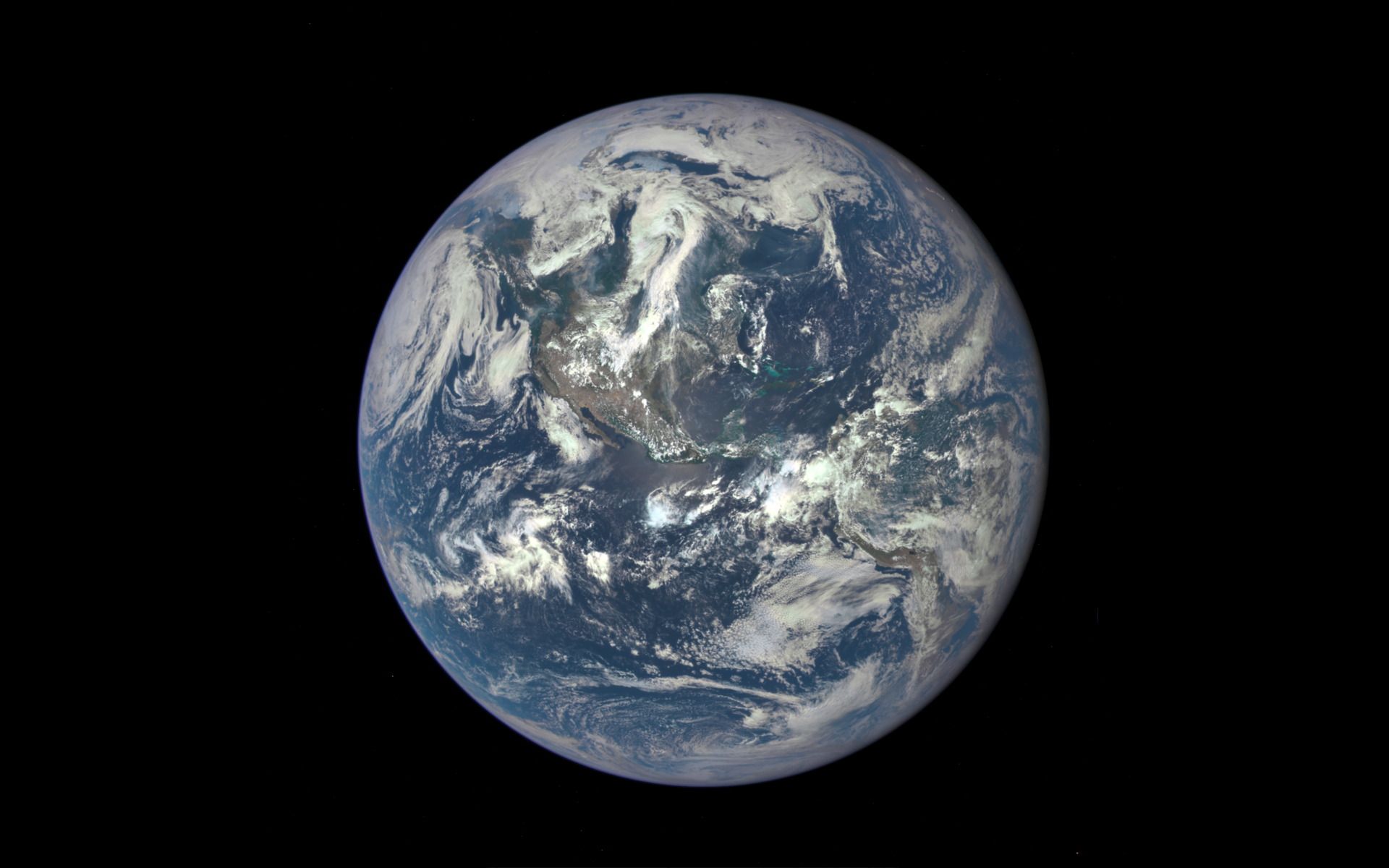

Life on Earth may exist thanks to an incredible stroke of luck — a chemical sweet spot that most planets miss during their formation but ours managed to hit.

A new study shows that Earth formed under an unusually precise set of chemical conditions that allowed it to retain two elements essential for life as we know it: phosphorus and nitrogen. Without a perfect balance of these elements, a rocky planet could appear habitable on the surface yet be fundamentally incapable of supporting biology, according to the study.

Earth seems to have hit this delicate chemical sweet spot during its formation nearly 4.6 billion years ago, and the new findings could change how scientists search for alien life, the researchers said.

When young planets form, they are often partially or fully molten. As heavy metals sink inward to form a core, lighter materials remain closer to the surface. During this chaotic stage, known as core formation, the amount of oxygen present plays a decisive role in determining where other elements end up — and whether they remain accessible for future life.

The study suggests that oxygen levels must fall within a surprisingly narrow range for both phosphorus and nitrogen to stay in a planet’s mantle and crust. Too little oxygen, and phosphorus bonds with iron and is dragged into the core, depriving the surface of a key ingredient for DNA, cell membranes and energy transfer. Too much oxygen, and nitrogen is more easily lost to space. Either way, the chemistry needed for life never fully comes together.

Using models of planetary formation and geochemical behavior, the researchers found that Earth sits squarely inside this narrow range of medium-level oxygen, which they called the chemical Goldilocks zone. Ultimately, our planet retained enough phosphorus and nitrogen to later fuel biology — a result that may be far from common among rocky worlds.

“Our models clearly show that the Earth is precisely within this range,” Walton said in the statement. “If we had had just a little more or a little less oxygen during core formation, there would not have been enough phosphorus or nitrogen for the development of life.”

Conversely, the researchers also modeled the formation of other planets such as Mars, where oxygen levels were outside this chemical Goldilocks zone. On Mars, for example, the models show more phosphorus in the mantle than on Earth, but less nitrogen, creating challenging conditions for life as we know it, according to the statement.

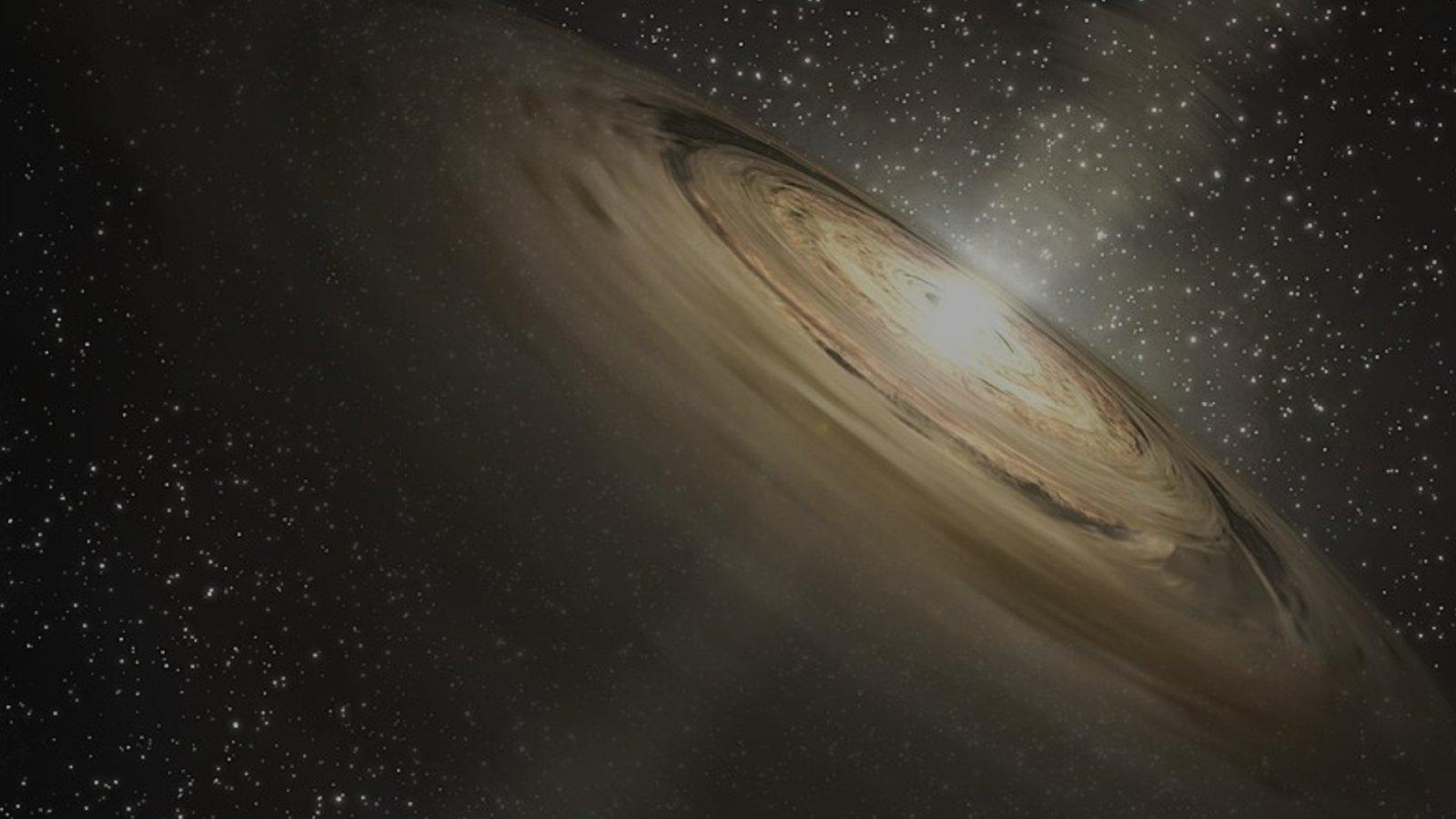

The findings challenge the traditional focus on the habitable zone, the region around a star where liquid water can exist. While water is critical, the study suggests it may be only part of the story. A planet could orbit at the right distance from its star and still lack the internal chemical inventory required for life to ever emerge.

Crucially, the oxygen conditions that shape this process are linked to the chemical makeup of the host star itself. Because planets form from the same material as their stars, stellar chemistry can hint at whether a system is even capable of producing life-friendly planets in the first place.

If the researchers are right, Earth may be less a cosmic norm and more a fortunate exception — a planet that hit a rare chemical jackpot early on. Using Earth as a benchmark could help scientists zero in on exoplanets that are the most likely to have the perfect balance of elements essential for life.

“This makes searching for life on other planets a lot more specific,” Walton said. “We should look for solar systems with stars that resemble our own sun.”

Their findings were published Feb. 9 in the journal Nature Astronomy.