Tropical Storm Fernand, which developed on Saturday night southeast of Bermuda, is the Atlantic’s second system in a row that will avoid a direct landfall. As of 11 a.m. EDT Monday, Fernand was about 425 miles (685 kilometers) east-northeast of Bermuda, heading north-northeast at 13 mph (20 km/h). Fernand’s top sustained winds were up to 60 mph (95 km/h).

Fernand was a highly asymmetric storm on Monday. As evident in the image at top, Fernand’s intense core of showers and thunderstorms was displaced southeast of the storm’s center. The northerly wind shear of around 15 knots that’s helping to tilt Fernand is expected to continue through Tuesday. Moreover, as Fernand moves into the midlatitudes, the sea surface temperature beneath its track will drop from around 28 degrees Celsius (82 degrees Fahrenheit) on Monday to around 26°C (79°F) on Tuesday. These factors are predicted to keep Fernand just shy of hurricane strength as it churns harmlessly through the open Atlantic. Fernand will encounter much cooler waters on Wednesday, when it’s predicted to become post-tropical.

Once Fernand is out of the picture, there’s nothing else of immediate concern brewing in the Atlantic tropics for at least the next week, according to the 8 a.m. EDT Monday Tropical Weather Outlook from the National Hurricane Center. Longer-range signals from ensemble weather models, as well as an unfavorable mode of the Madden-Julian Oscillation, suggest that the quietude could extend beyond the U.S. Labor Day holiday weekend.

This calm spell will be worth appreciating, since we’ve just entered the eight-week period when the Atlantic season typically hits its peak. There’s ample warm water to fuel storms through the Atlantic tropics, and the central and eastern tropical Pacific is continuing to move toward La Niña conditions, which could help favor activity in the Atlantic well into autumn.

In their two-week forecast issued on August 20, the tropical weather group at Colorado State University said: “The most recent seasonal forecast calls for an above-average season. We still believe that this forecast will verify, but we are anticipating a downturn activity relative to climatology during late August/early September.”

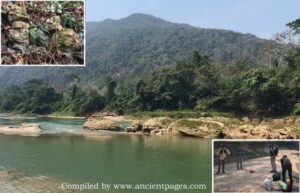

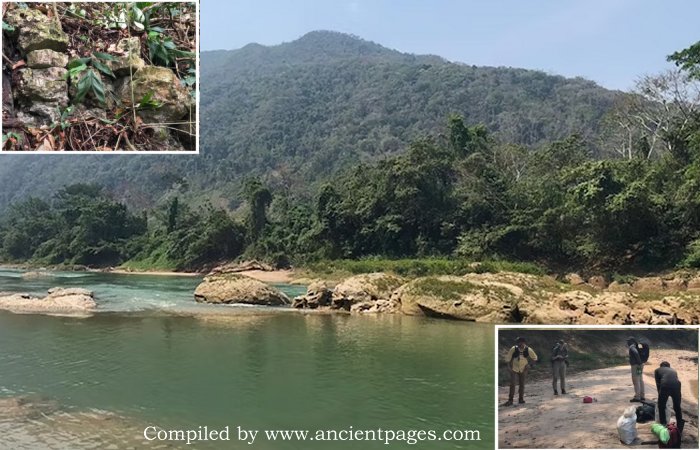

Typhoon Kajiki slides into northern Vietnam

The planet’s most significant landfalling storm in recent days, Typhoon Kajiki edged onto the coast of northern Vietnam between Vinh and Ha Tinh around 8Z Monday (4 a.m. EDT). Kajiki made landfall with top sustained winds of 105 mph, making it a Category 2-equivalent. There were no immediate reports of fatalities or major damage from Kajiki. Hundreds of thousands were evacuated ahead of the typhoon, with memories still fresh from the devastating hit of Supertyphoon Yagi in 2024. Yagi took more than 300 lives in Vietnam and more than 400 in Myanmar.

Localized rainfall amounts could reach 20 inches (508 mm) as Kajiki’s circulation pushes inland and crosses the rugged terrain of northern Vietnam and Laos. Before reaching Vietnam, Kajiki passed just south of China’s Hainan Island, putting the island on its stronger right-hand side and bringing sustained winds that topped 100 mph.

In the Eastern Pacific, Tropical Storm Juliette was gradually strengthening on Monday after forming on Sunday. Juliette is predicted to take a northward-arcing track well off the coast of Mexico and is not predicted to reach hurricane strength before dissipating late in the week.

Dying young: Tropical cyclones across the Northern Hemisphere have trended unusually brief this year

Tropical areas north of the equator have been spitting out as many tropical storms and hurricane-strength cyclones in 2025 as they do in a typical year. Weirdly, though, they’re simply not lasting all that long, and the very strongest ones have been sparse.

As of August 25, statistics from Colorado State show that the Northern Hemisphere has produced 32 named storms to date (average to date is 29.2) and 14 hurricane-strength cyclones (average to date is 14.8). However, the number of hurricane days (calculated by totalling the duration of each hurricane-strength system) was only 23.25, compared to the average to date of 46.8. The hemisphere has produced only four tropical cyclones as strong as a major hurricane, compared to the average of 7.1, and the number of major hurricane days, 4.75, is far below the average to date of 15.6.

All told, the accumulated cyclone energy, or ACE, for the Northern Hemisphere – a measure of both peak wind speeds and duration – was at 139.7 on August 25, compared to the average to date of 223.4. Both the Northeast and Northwest Pacific were far below their average ACE, and there has yet to be a named system in the North Indian Ocean.

Only the Atlantic is (finally) running above average on ACE in the wake of Erin’s impressive run, as evident in Fig. 1 above. The Atlantic ACE to date of 37.1 compares to the average of 24.9. But with a quiet last week of August in store, ACE levels may drop below average by early September.

Jeff Masters contributed to this post.