The natural world is built for change. Seasons shift. Rivers rise and fall. The climate gradually warms and cools again. Animals migrate, adapt, and evolve in response to these rhythms. This is how Earth has always worked – and how it’s supposed to work.

The pine forests of the Western U.S. offer a perfect example. For thousands of years, ponderosa and lodgepole pines evolved with periodic wildfires that swept through every decade or two. These fires weren’t disasters – they were essential.

Lodgepole pines actually depend on fire to reproduce. Their resinous cones only open in intense heat, releasing seeds onto the ash bed below. Ponderosa pines developed thick, fire-resistant bark to survive the low-intensity ground fires that cleared out undergrowth. These frequent, cool burns created open forests with widely spaced mature trees, healthy and highly productive ecosystems that provided clean water, timber, and wildlife habitat.

So the problem today isn’t change. It’s the speed of change.

Changes that used to take centuries or millennia are now unfolding in a matter of years. Levels of climate-warming carbon dioxide in the atmosphere have risen to well above 400 parts per million, a concentration that last occurred about 15 million years ago.

But even more concerning is the rate of change: By burning fossil fuels, we are emitting carbon dioxide into the atmosphere 30 times faster than at any point in the last 100 million years. That’s like putting nature’s slow-moving film on fast-forward – only the device is overheating as a result.

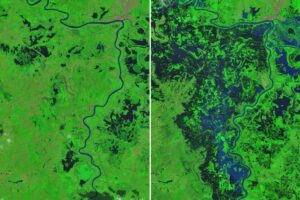

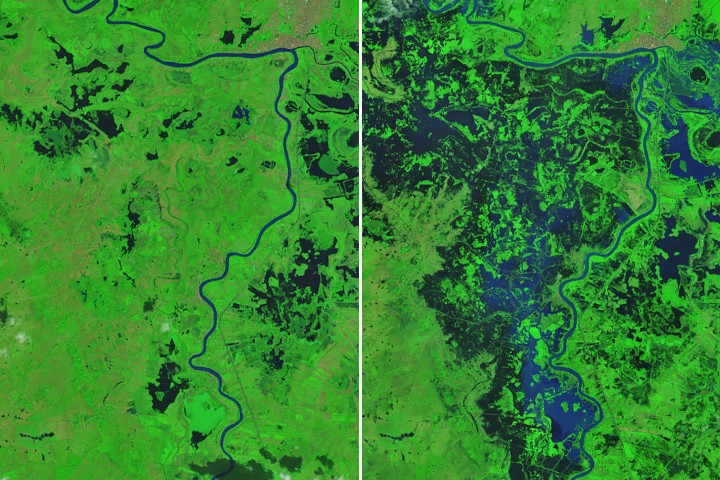

And it’s not just temperatures rising. Seasons are shifting, and so are disturbance patterns – wildfires, floods, heat waves, and high winds. These changes are moving faster than the systems designed to handle them.

Animals we need and love are being pushed to the edge

Take the wildlife we all cherish – monarch butterflies, hummingbirds, sea turtles, salmon, moose. They’re caught in a high-speed game of catch-up.

Birds arrive for nesting season only to find the insects they depend on already came and went. Moose in the north are dying from parasite overload because winters are no longer cold enough to kill off ticks. Salmon, not only one of the most healthy and delicious fish but also one of the most culturally and ecologically important species in the West, are swimming in rivers that are increasingly too warm to survive. Monarch butterflies, which used to be abundant across North America, are now likely to go extinct in the coming decades due to multiple threats, including hotter and more erratic weather from human-caused climate change.

Even the livestock and pollinators we depend on – cattle, bees, sheep – are feeling the hit. Heat stress reduces milk production, wildfires destroy grazing lands, and altered flowering seasons break the link between bees and the plants they pollinate.

Nature can adapt. But not overnight. Adaptation takes time, and time is exactly what we no longer have.

We’re breaking the shock absorbers

The natural and built systems around us – forests, farms, rivers, cities, insurance markets – are all designed with buffers, with the expectation that shocks will come occasionally. But now, the shocks are constant.

Consider wildfires. A century of fire suppression combined with rising temperatures and prolonged droughts has turned beneficial ground fires into catastrophic fires that spread to the tops of trees and shrubs. What used to be a gentle clearing burn that most mature trees survived now becomes an inferno that sterilizes entire mountainsides. And the forest understory, once cleared regularly by small fires, is now loaded with decades of accumulated fuel and invasive species.

Meanwhile, the timing is all wrong – fires now burn hotter and longer into the fall, when trees are most vulnerable and recovery conditions are poorest. Even lodgepole pines can’t regenerate when fires burn so intensely that they destroy the soil itself. It’s like a car’s shock absorbers being asked to handle potholes at highway speeds – they simply can’t absorb impacts coming that fast and that hard.

With laws like the Inflation Reduction Act and programs like the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities, we had mapped out an off-ramp. These policies would have helped the U.S. cut its climate-warming emissions, support communities, and build resilience. But just as we approached the exit, the Trump administration tossed the map out the window, turned the headlights off, and hit the accelerator on the road of a rapidly changing climate.

This isn’t a metaphor anymore. It’s policy.

What we do next matters

This is why adapting to climate change is not enough. We can’t just plant more drought-resistant crops or assume that nature will catch up. We must slow down the system. That means cutting the emissions that are driving this acceleration – rapidly and boldly. It means installing more wind turbines, solar panels, and using more energy-efficient appliances. It means eating more plant-based foods and less beef and pork, which will also make us healthier and save water.

We need policies that match the scale of the problem – not those that pretend it’s not that bad or that the solutions are too costly. Because right now, nature’s trying to keep up with a system that’s being pushed beyond its breaking point. We can still choose a different road. But not if we keep blowing past the exits.