Summary

- Consume sleep trackers offer a rough approximation at best, since they can’t directly monitor brain activity.

- Results also vary widely among different trackers, owing to differing algorithms and sensors.

- Consistency within a single device can still provide helpful cues to improve your sleep habits or detect potential health issues.

In another recent piece, I mentioned that one of the features I’ve enjoyed most since getting an Apple Watch Ultra 2 is actually its sleep tracking. It helps that the Ultra line actually has enough battery life for it, unlike other Apple Watches, which may need to be charged twice a day for overnight wear to be viable. More to the point, knowing how long and well you’re sleeping can prompt you to make lifestyle changes that legitimately improve your health.

There’s something critical to be aware of, however: you shouldn’t take sleep tracking data at face value, whether it’s from a smartwatch, a smart display, or even a dedicated sleep tracking device like Garmin’s new Index Sleep Monitor. It’s often one of the weakest aspects of fitness on consumer devices.

- Brand

-

Apple

- Heart Rate Monitor

-

Electrical and optical

- Color Screen

-

3000nits

- Battery Life

-

Up to 72 hours

Related

Does smart tech really add that much to your fitness regimen?

The full answer varies from person to person, but here’s my gym-buff take.

What are sleep trackers actually tracking?

You can’t fit a lab on your wrist

The first thing to be aware of is that, as Johns Hopkins notes, most consumer devices don’t actually monitor sleep directly. In a lab, sleep tracking is done by measuring brain waves, which are the true gauge of what sleep phase you’re in. There are four phases in all: N1, N2, N3, and REM, each deeper than the last, with progressively slowing brain activity apart from the dreaming you do during REM.

Because most consumer trackers don’t have you applying EEG sensors to your skull, they have to use stand-ins that correlate to the different phases in a loose way. One of these is motion — the deeper the sleep, the less likely you are to shift around or breathe rapidly, and, of course, someone who’s actively tossing and turning may be awake. Smartwatches and similar devices typically rely on accelerometers to collect motion data, but other methods are available. Google’s second-generation Nest Hub, for example, uses short-range radar to gauge both your position and how well you’re breathing.

Most consumer devices don’t actually monitor sleep directly.

Even more important than motion in many cases is your heart rate. Your heartbeat slows during deep sleep, though it may pick up again during REM. Of special interest is heart rate variability, the gap between minimum and maximum heart rates — this shifts as you progress through each phase.

Some devices monitor other sleep factors. One is blood oxygen, which should dip during sleep, but may (along with irregular breathing patterns) be an indicator of trouble like sleep apnea if it drops too far. A number of products may also be able to detect abnormal light, sound, and/or temperature levels, possibly including your skin temperature. This data probably won’t tell you anything about phases, but it can suggest why sleep was bad or interrupted — snoring and overly hot rooms are common culprits.

Related

4 tech devices I always take on flights no matter what

It’s hard to imagine longhaul flights without these gadgets.

Why you can’t really trust consumer sleep trackers

Different algorithms, different results

As you may have gathered, the primary issue is the loose correlation I mentioned. You are, at best, getting a reasonable approximation of sleep, much in the same way that heart rate data will get you a rough estimate of calorie burn. Your tracker could easily be way off, especially if a device has inferior sensor technology, or one or more sensors are briefly interrupted. A device on your wrist or arm will naturally shift around unless you cinch its band tight — and most people aren’t going to do that if they want to be comfortable. Some people can’t even fathom wearing anything as bulky as an Ultra 2 to bed, given how it might get caught on bedding or press into their arm. I haven’t had many comfort issues personally, but I get the apprehension.

You are, at best, getting a reasonable approximation of sleep, much in the same way that heart rate data will get you a rough estimate of calorie burn.

Moreover, there’s no standard algorithm for translating data. While there might be common scientific principles involved, device makers naturally have to tweak their algorithms on a per-device basis for the sensors they’re using, and there may be a little English applied on top of that — to borrow a pool term.

The consequence is that two sleep trackers can produce wildly different results, even when they’re worn for the same night’s sleep. I’ve seen this myself, having reviewed or owned a variety of wearables since the mid-2010s. There’s rarely any match in the times you fall asleep and wake up, much less in what sleep phases look like.

Some companies, such as Apple, insist that you input a standard sleep schedule into their apps, using this as a crutch to inform their algorithms. Indeed, it’s only in the past few years that automatic nap tracking has become commonplace — Apple waited until 2024’s watchOS 11 update.

Related

4 missing features I can’t believe the iPad still doesn’t have

Apple is making a real leap forward with iPadOS 26, but many of us still have a wishlist.

So why use sleep tracking at all, then?

The theory of relativity

Apple/Pocket-lint

The answer is that, as long as you’re using the same device, sleep tracking can provide relatively consistent results worth taking action on. Any tracker is going to have an error margin versus your real sleep duration — but if that margin is mostly consistent, it’s still going to mean something when an app says you slept seven hours one night but only six the next. It’s a cue to get to bed earlier and/or tackle other issues that might be interfering, especially if you’re getting substandard numbers over the course of a few weeks.

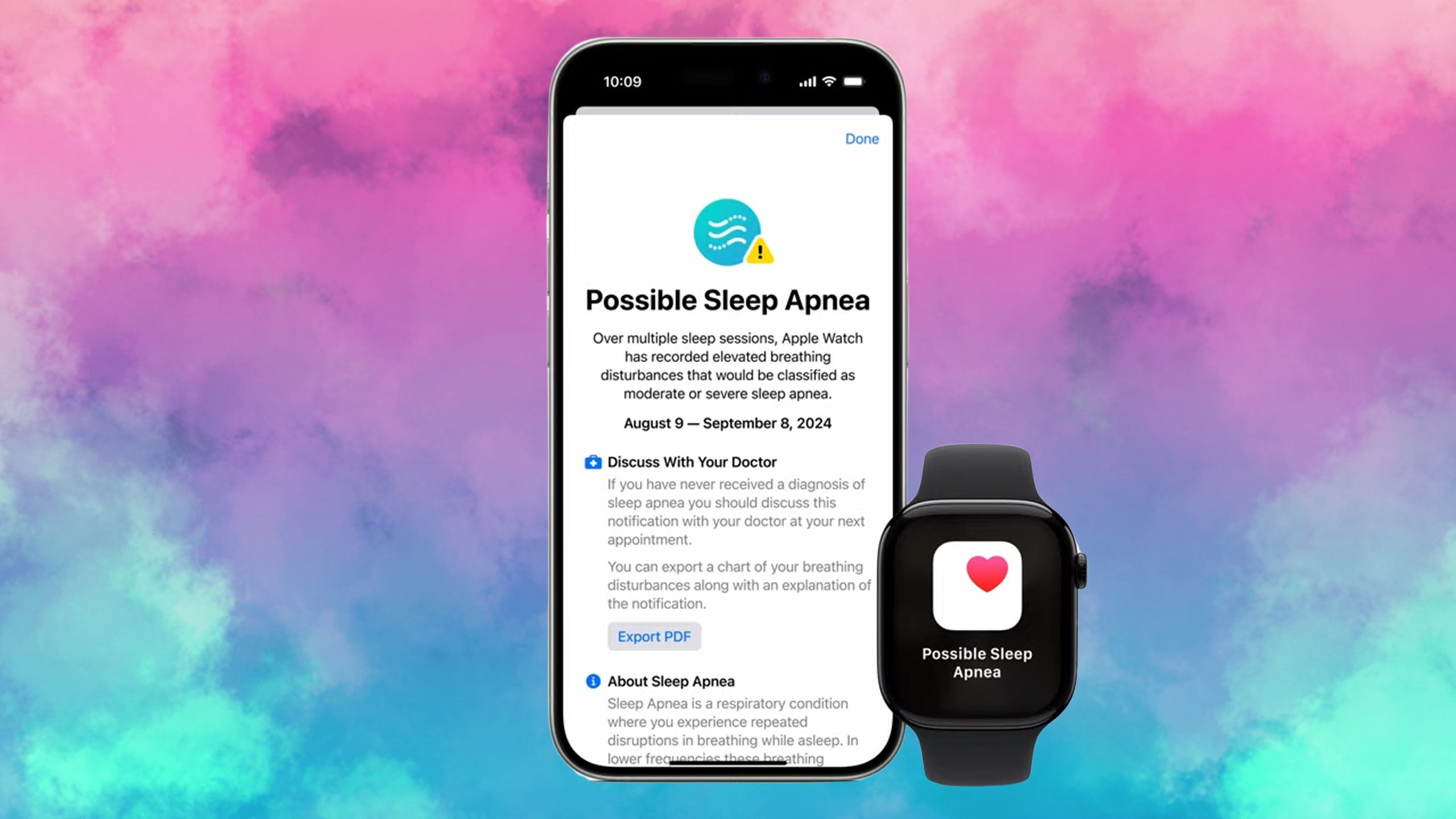

If nothing else, warnings about medical conditions can potentially be lifesaving, or at least life-altering.

Likewise, while I don’t put much stock in phase detection on consumer devices, there seems to be enough consistency on a single device that it’s worth paying attention to if an issue pops up repeatedly. Recently, for example, I’ve had trouble with waking up 35 to 50 minutes before my alarm goes off. This happens nearly every morning. As it turns out, Apple Health says I’m always in REM during these incidents — probably reflecting stressful dreams and my general anxiety. I’ve had some luck countering this with sleeping pills, intentional calming techniques, or simply wearing myself out as much as possible before I go to bed.

If nothing else, warnings about medical conditions can potentially be lifesaving, or at least life-altering. You may or may not have sleep apnea if a notification pops up on your watch — but there’s probably some sort of root issue, and you’ll be prompted to see a doctor who can help with a clinical diagnosis. It’s better to waste time discovering a tracker is flawed than to find out the hard way that you’re not breathing at night.

You might also like

Everything you need to know about PEVs, or personal electric vehicles

You can use PEVs like e-bikes and scooters to explore, run errands, or speed up your commute.